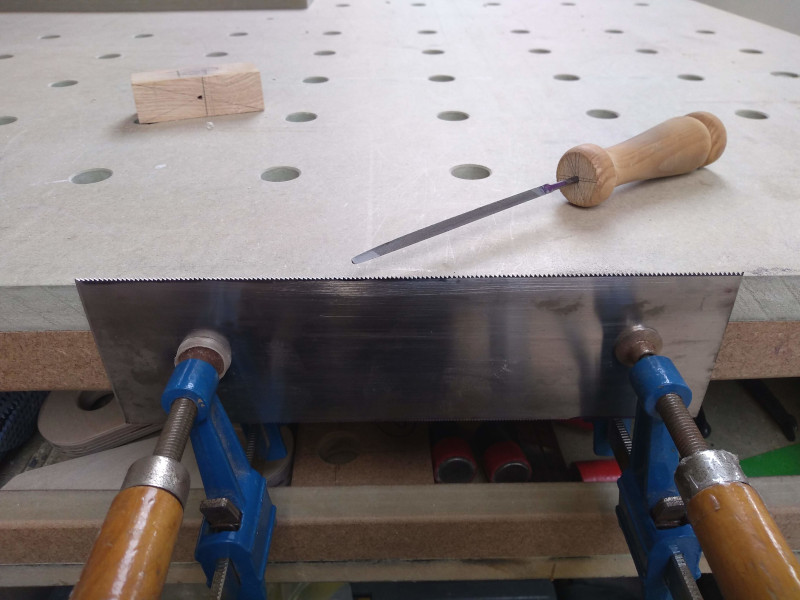

HH, yes, you can remove folded backs fairly easily from most saws, though it's sometimes not "easy". Apart from corrosion, which can make them very hard to budge innitially, there does seem to be a bit of variability between how tight they were when first fitted. I haven't adjusted enough spines on enough saws to have any idea if the variation is random or if some brands were more careful when fitting spines.

I was unaware of Skelton saws until you mentioned them, so yesterday, I spent some time on their website. If you have a very generous tool budget & want a tool to brag about, they have much to offer. However, I have mixed feelings about tools like these. As someone who has made many saws, I admire & fully appreciate the workmanship & the thought that's gone into them, but that tensioning system is rather overboard & quite unnecessary, imo. If your back is reasonably tight, and you tap the blade back 10-15 mm when fitting it as I mentioned previously, you'll introduce the tiny amount of tension required. It will be quite sufficient for sawing any wood, from the hardest known (of which we have numerous examples where I live!) to the softest. Unlike with a bandsaw blade, for e.g., the amount of heat generated when sawing is highly unlikely to cause warping unless you like zero set & use a very frenzied sawing action.

I can't remember where I saw the article, but I think it might have been in a very old Fine Woodworking, where an 'old-timer' (& that was 35- 40 years ago) was talking about refurbishing old backsaws. He talked sbout the function of the spine & showed an example of a warped-looking blade that he "fixed" by tapping the spine about a bit to set it properly. That opened my eyes to the fact that the spine does a bit more than passively holding the blade straight. But you can easily achieve these ends without having to introduce extra tensioning devices - a cool bit of engineering & superbly executed, but totally OTT (again, imo!).

I think you've shown a lot of practicality and common-sense in your approach to tool-making, & we've found similar solutions to the same problems, but you seem to have progressed more rapidly than I did - it has taken me many years to figure out some of the basics. But stick with the common-sense approach, I say. If a certain design has been static for 200 years, it's a good indication that it's because it does a very good job & there is really no need for further refinement. Not always, of course, & I'm sure there are examples to the contrary, but it should give us pause to think if our 'improvements' are either necessary or desiraable.

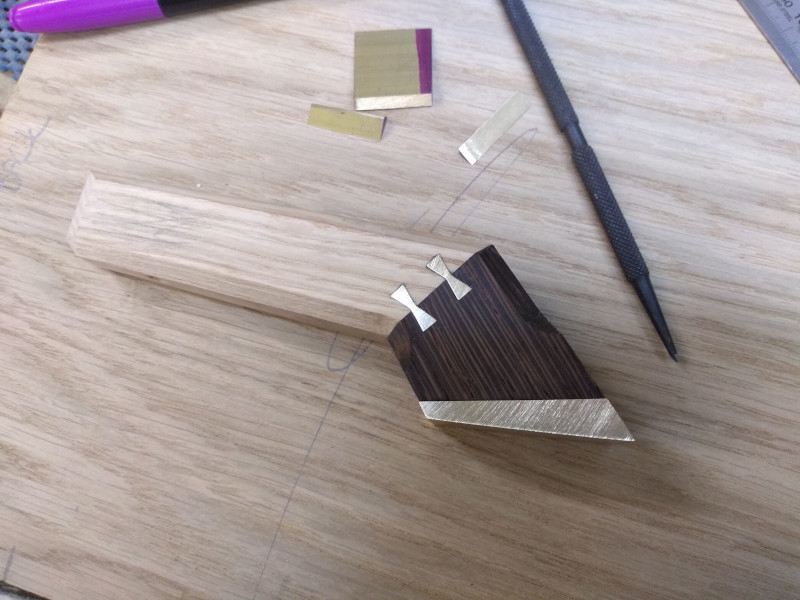

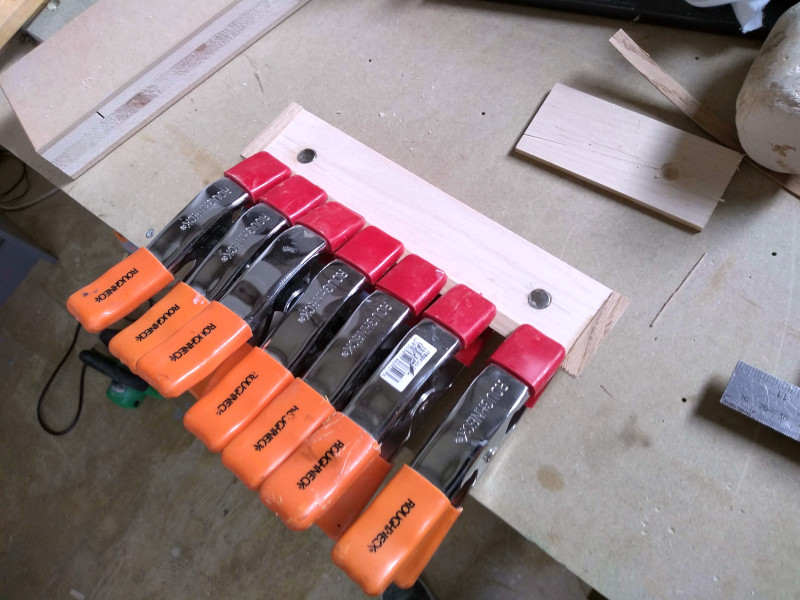

I talk from the perspective of a tool-user rather than a maker. I've made at least 50 saws by now, and the last dozen were definitely better than the first few, the fit of spine & blade is hard to get perfect in the silly hard (but highly attractive!) woods I choose to use, but is one thing you do need to get right in order to have a solid, straight saw. Those Skelton saws are exemplary in that respect, thanks to some neat machining. The other really important part is the grip angle & position. The Skelton dictum that it should be set so your index finger points to the centre of the tooth line is rather simplistic. It is all about smooth transfer of power to the tooth line, which really depends on what height you use a saw at.

For years I had an absolute favourite dovetail saw. It was a Tyzack, acquired bout 1980. It came with an excuse for a handle, which I hated both the look & feel of, and was quickly replaced with a handle copied from a friend's similar-sized 1920s Disston. With the new handle, it suddenly became my go-to saw for dovetailing, but it was at least 25 years later before I figured out why. By sheer fluke, I'd got he grip angle perfect for sawing at an elevated height as you do when sawing D/Ts or tenons. With this saw, my wrist is in a 'neutral' position as I begin the cut, which makes it comfortable & easy to control the saw intuitively. At the end of the cut, it's bang on the line front & back, almost no need to check. An old cabinet-maker who mentored me in my 20s used to insist I should saw tails & pins & just tap them together for a perfect fit - paring to fit was a waste of time & an admission of failure in his eyes. I struggled for many years to achieve this, but when that saw entered my life, it became easy. It was ousted a few years back by one I've made, which is fractionally better, it has a nicer handle that fits my hand a bit better, but what gives it the edge is that it has a lighter spine, which makes it easier to place & start for the left/right tail cuts. The Tyzack has a much wider, thicker & heavier spine, & now I'm used to my saw, I find it clumsy.

It's minor details like these that I think take a saw from good to excellent. But the paramount requirements of any saw is a straight blade, with a pitch & tooth conformation appropriate to the task, & above all,

sharp. Satisfy those criteria & I'll take bets I can split the line with just about any handle on it (even plastic

), but it will take much more concentration & I won't enjoy the task anywhere near as much.....

Cheers,