woodbrains

Established Member

Hello,

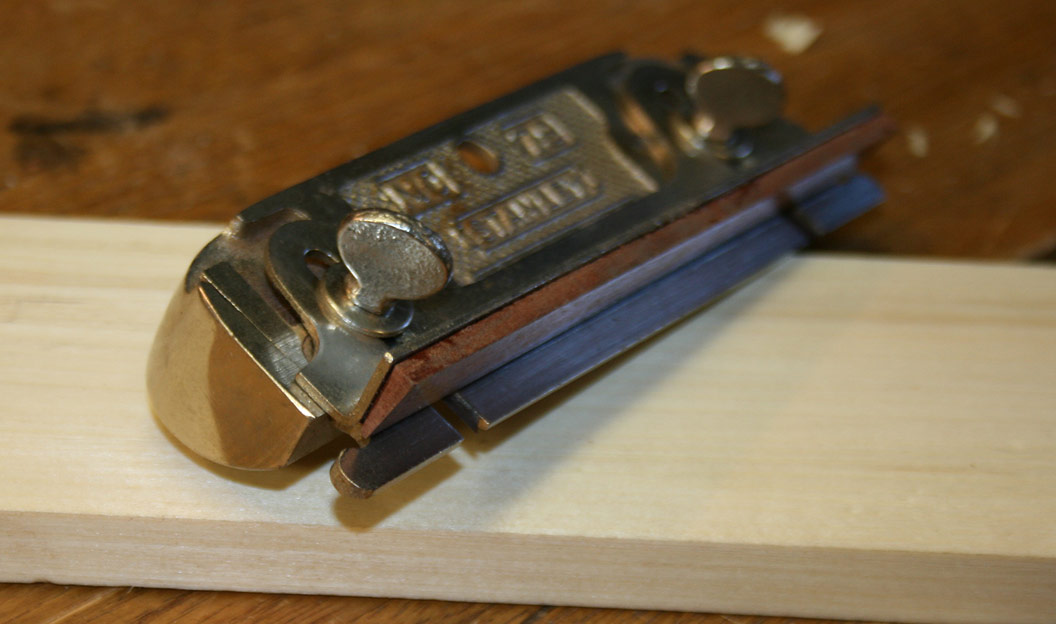

Planes exist for running the male portion of a sliding dovetail. In fact there are still some being manufactured in Europe as well as by specialist plane makers; Philly springs to mind. The only planes I know of, and I'm talking from a limited knowledge, for cutting the female portion, are japanese.

How do people here deal with the female part of this joint? It can be done with saws against an angled fence, router plane, snipes bill, side rebate plane, paring chisels......anyone have an ideal method, preferably one that is 'fine' looking on the show edge? Does anyone have a female dovetail plane? Commercial, vintage of user made.

Mike.

Planes exist for running the male portion of a sliding dovetail. In fact there are still some being manufactured in Europe as well as by specialist plane makers; Philly springs to mind. The only planes I know of, and I'm talking from a limited knowledge, for cutting the female portion, are japanese.

How do people here deal with the female part of this joint? It can be done with saws against an angled fence, router plane, snipes bill, side rebate plane, paring chisels......anyone have an ideal method, preferably one that is 'fine' looking on the show edge? Does anyone have a female dovetail plane? Commercial, vintage of user made.

Mike.