Following on from the Chisel quality ? thread, what if your chisel is too hard (brittle) or too soft? Do you live with it, shop around for alternatives or go with door number three?

The third option is the purpose of the thread and that is doing some heat treating of the steel yourself. This is not widely known about or the thought fills people with trepidation but it can be quite simple and straightforward as you'll see below, it can be done in the workshop or the kitchen using the most basic setup, e.g. a gas torch (butane, propane or MAPP) and a container of water.

Too brittle is the easiest to deal with. This can be simply tempered out of the steel by heating to lower, 'non-critical', temperatures – usually you're aiming for a surface oxidation of a yellowish or light straw colour – and even a cooker's gas burner is more than capable of providing enough heat for this. Almost any tool steel should respond to this treatment.

For too soft you have to re-do the heat treating from scratch, how-to on this is shown in the link and explained by the pictures below. All basic high-carbon tool steels can be hardened in this way and a few of the modern steels as well.

A demonstration of how easy this sort of thing can be is seen in this video, Small Woodworking Shop Tips & ideas from Jim Cummins, editor of Fine Woodworking, where he takes only a few minutes to re-do the heat treating on a chisel and a key point is he doesn't even need take the plastic handle off to do it. The video is an hour long so if you want to go directly to the relevant part here's a direct link.

Here are a couple of other references from publications for more details. Since both are American publications they give temperatures in Fahrenheit, 1450°F is 788°C.

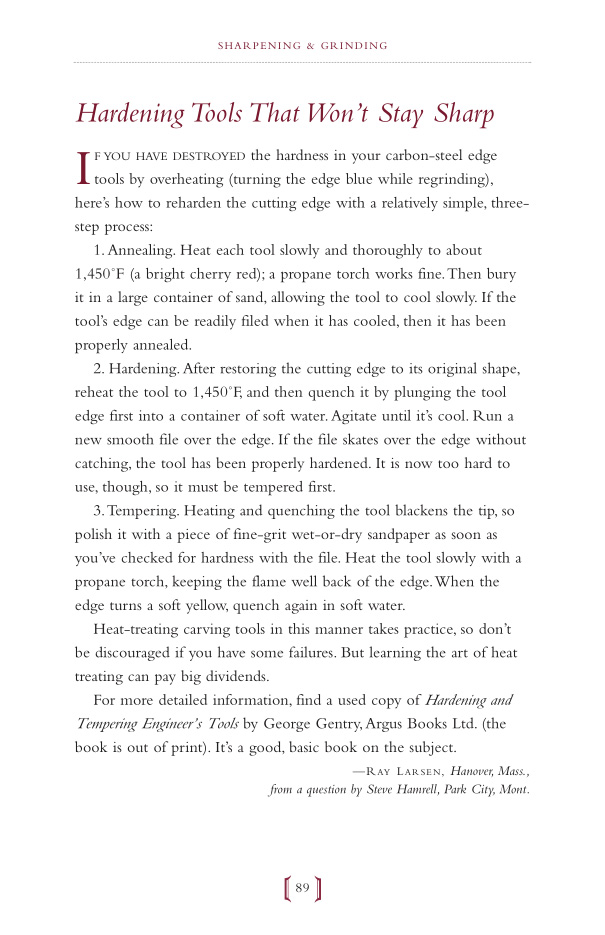

From "Best Tips From 25 Years Of Fine Woodworking":

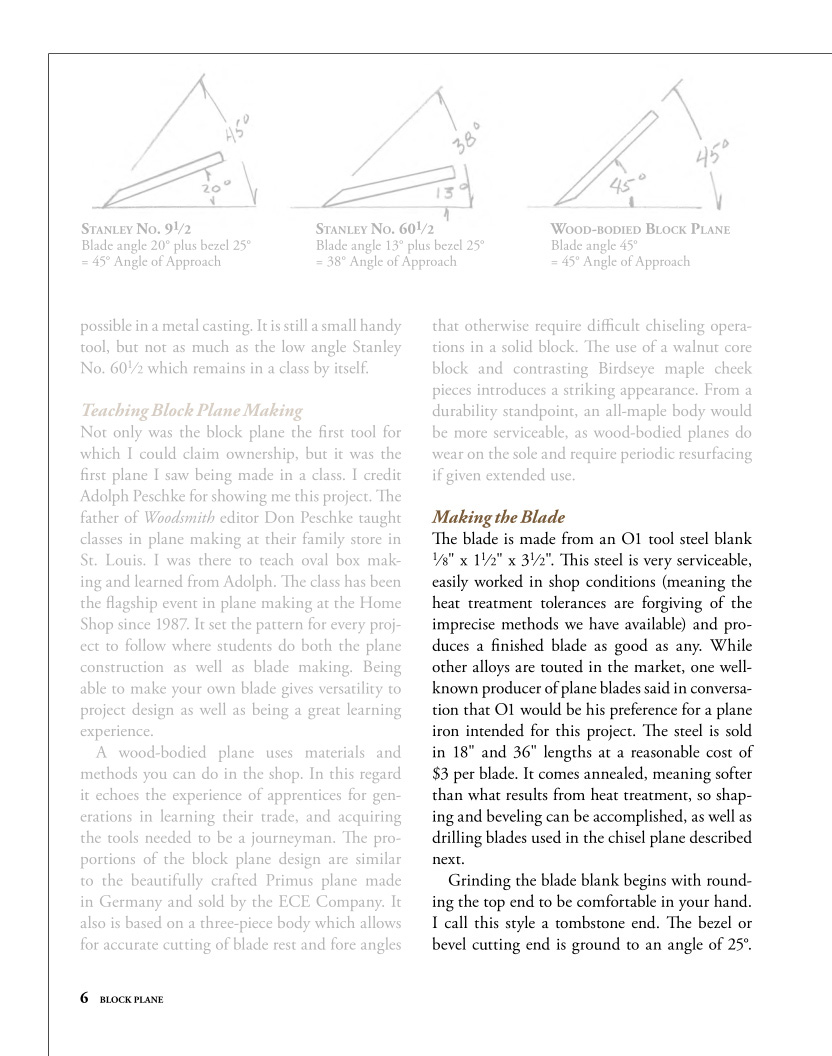

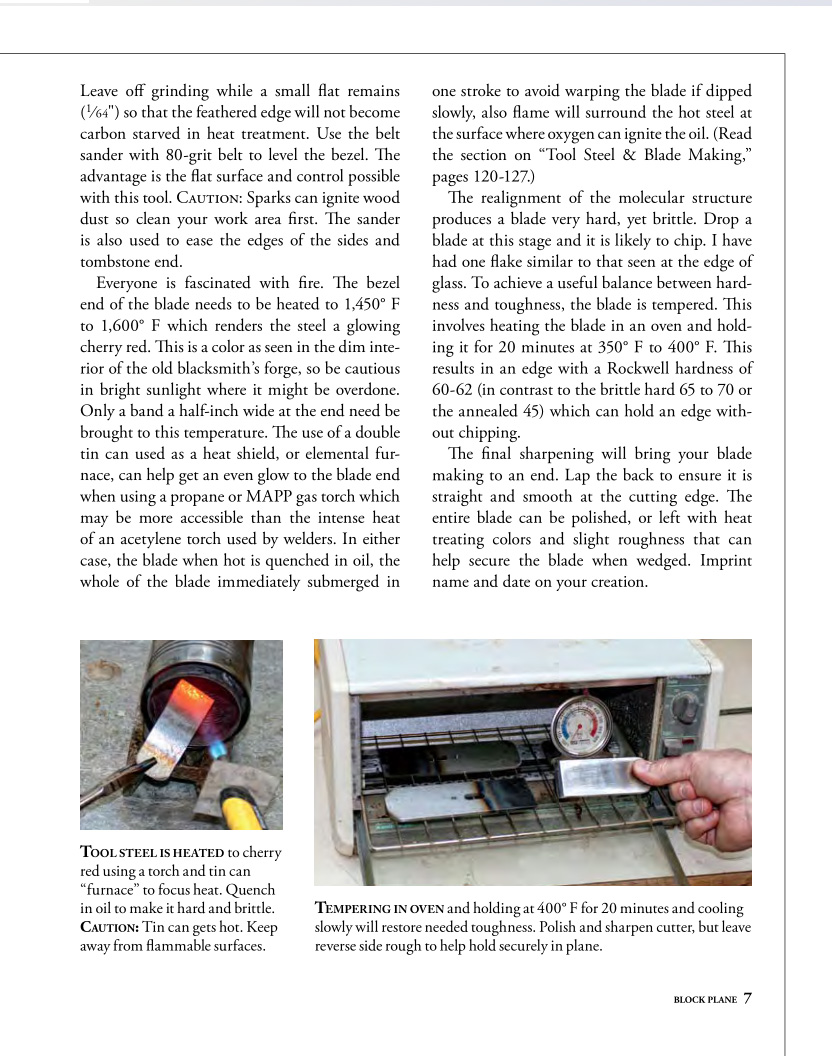

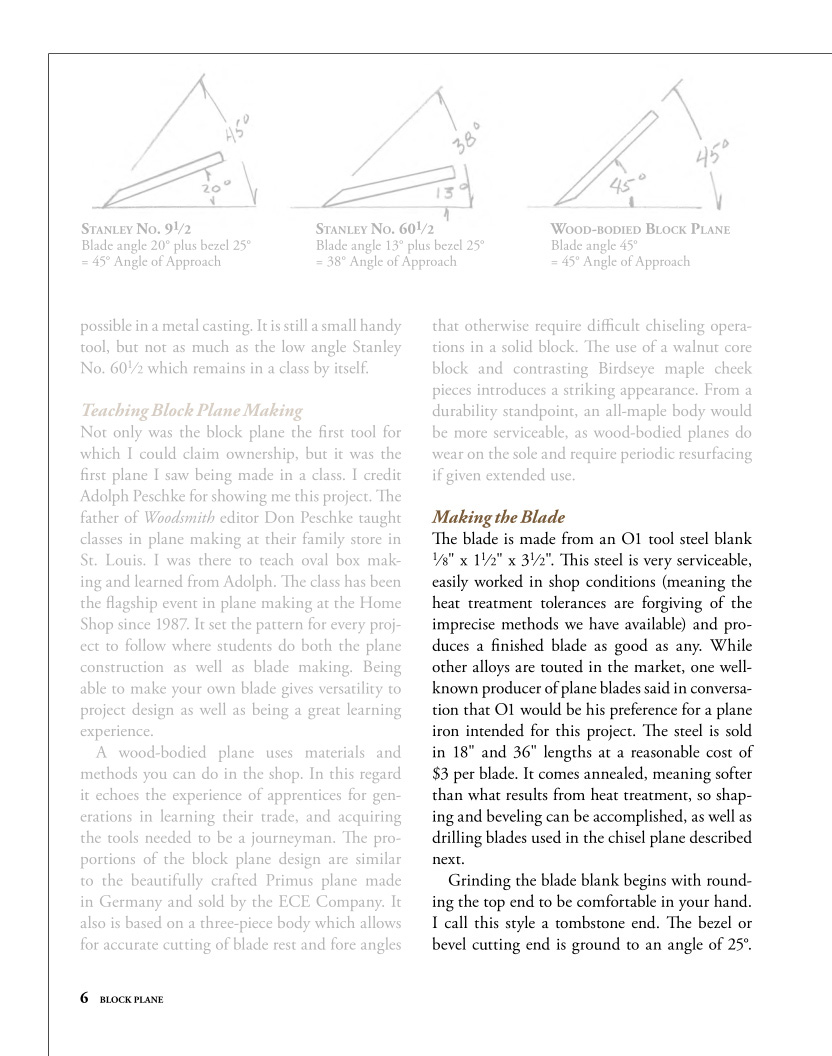

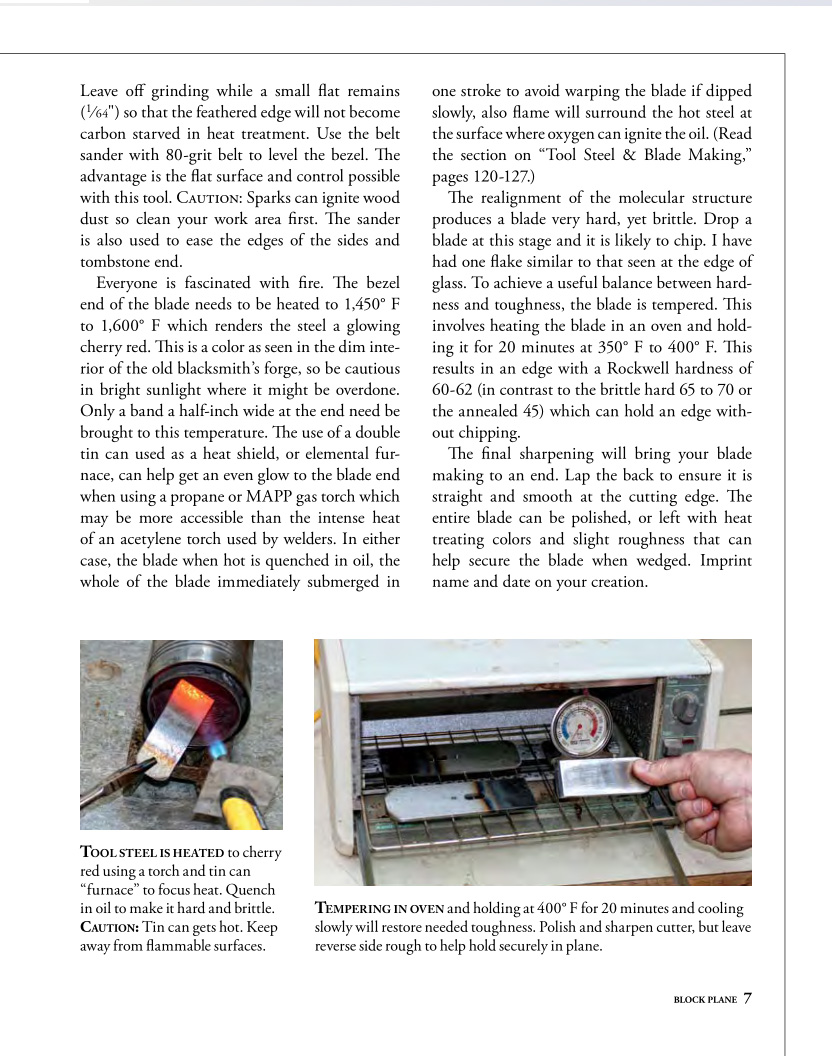

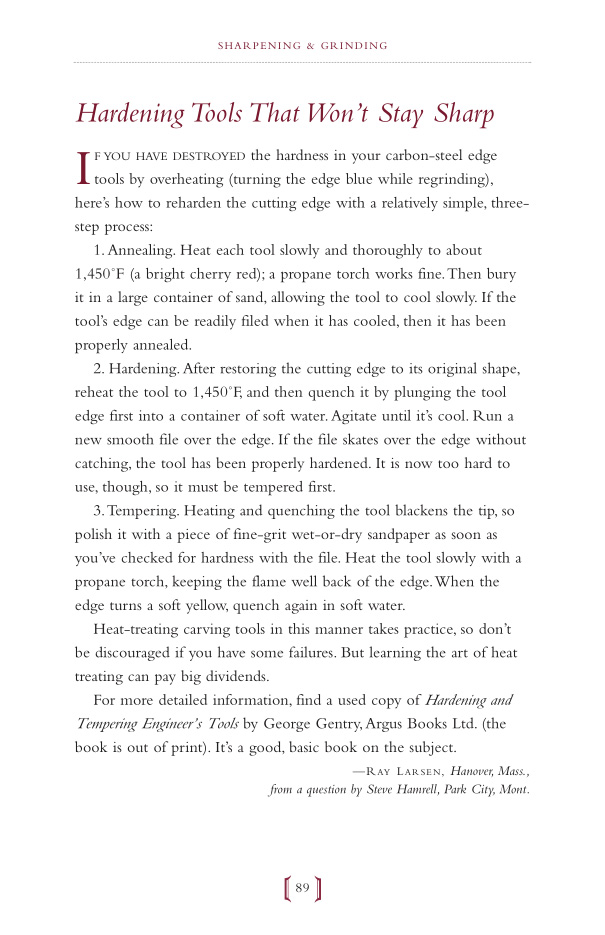

From "Making Wood Tools" by John Wilson:

The third option is the purpose of the thread and that is doing some heat treating of the steel yourself. This is not widely known about or the thought fills people with trepidation but it can be quite simple and straightforward as you'll see below, it can be done in the workshop or the kitchen using the most basic setup, e.g. a gas torch (butane, propane or MAPP) and a container of water.

Too brittle is the easiest to deal with. This can be simply tempered out of the steel by heating to lower, 'non-critical', temperatures – usually you're aiming for a surface oxidation of a yellowish or light straw colour – and even a cooker's gas burner is more than capable of providing enough heat for this. Almost any tool steel should respond to this treatment.

For too soft you have to re-do the heat treating from scratch, how-to on this is shown in the link and explained by the pictures below. All basic high-carbon tool steels can be hardened in this way and a few of the modern steels as well.

A demonstration of how easy this sort of thing can be is seen in this video, Small Woodworking Shop Tips & ideas from Jim Cummins, editor of Fine Woodworking, where he takes only a few minutes to re-do the heat treating on a chisel and a key point is he doesn't even need take the plastic handle off to do it. The video is an hour long so if you want to go directly to the relevant part here's a direct link.

Here are a couple of other references from publications for more details. Since both are American publications they give temperatures in Fahrenheit, 1450°F is 788°C.

From "Best Tips From 25 Years Of Fine Woodworking":

From "Making Wood Tools" by John Wilson: