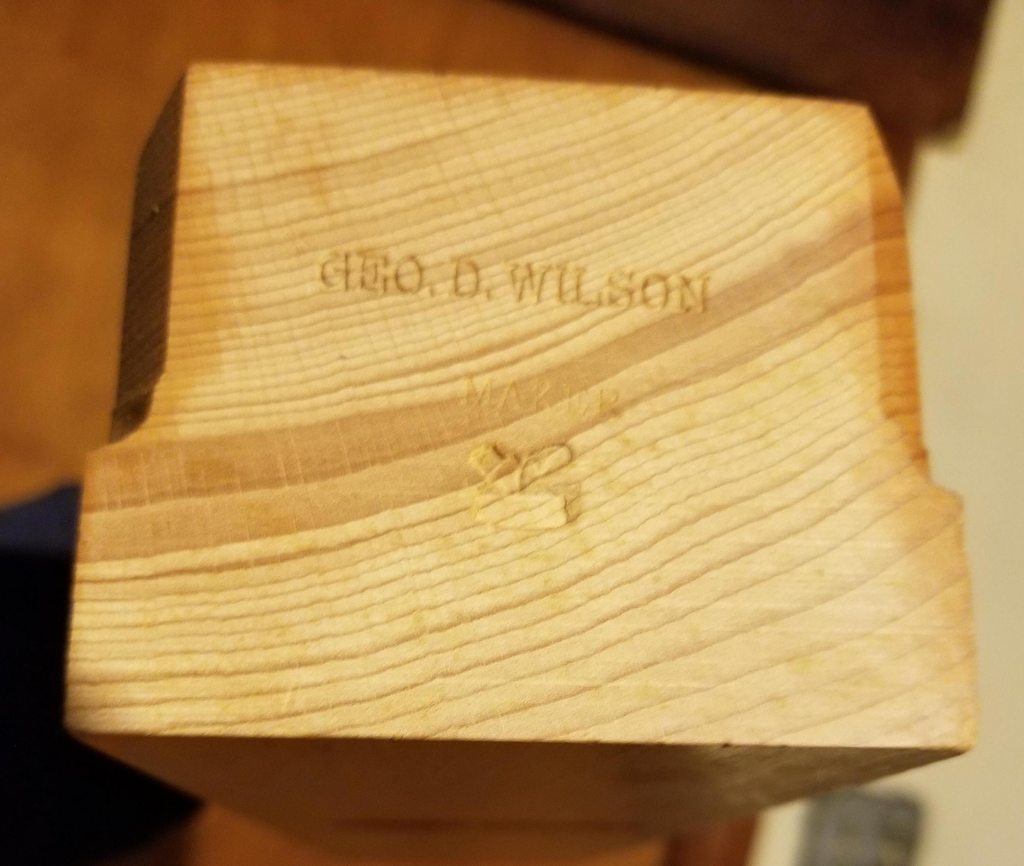

I am an amateur wooden plane maker, which is probably a known thing, but I settled on English style double iron planes to make as a matter of productivity. I've posted some pictures of planes before. One will be here, but one I don't use much.

My wife is on my case to trim my piles. I don't sell off much of anything without setting it up because most people don't know how to adjust a plane like this when it hasn't been used for decades. Once I set the planes up, I hate selling them, even though I've made my own.

I can't figure out how to post picture links from the imgur app, so I'll just share the gallery.

The joy of working with wooden planes

https://imgur.com/gallery/KgTW24k

This is work to come up with moulding stock. I've only been in the shop a half hour a day lately, and I haven't been getting much done because of it. Today was the same story.

Someone asked in the owt thread what the big deal is with cap irons when bu planes work so well. This is an example of it, cleaning up rough stock to be marked out and struck later.

Huge 10 to 14 thou shavings 2 1/8th wide taken at a lazy pace and smoother shavings about half that. Not even enough work to break a sweat, but I tried this in the past with bu planes and it was pure hell.

I made the cocobolo coffin smoother early on when trying to figure out how to make double iron planes well and the ih sorby iron in it is a little softer and not good at holding a fine edge, but it will take thicker shavings for eons, so I dedicated it to this. It is magic for machine planed wood, too. Chatter and evidence of any crushing or compression is gone in one or two passes with a near finished surface left behind.

For this kind of work in medium hardwoods, these types of planes are unequaled and this type of work will teach someone much faster methods of smoothing than taking tons of tiny shavings and getting sweated up. The cap iron makes it risk free.

The smoother even in this case will remove the sawmill marks from the rough side of the sticking in 8 strokes each side.

Keeping the thick shavings continuous and avoiding tearout keeps the plane so engaged that nothing but a round dog is needed at one end, and no constraints on the other.

As to why I made a big 2 1/4 inch smoother that is 4 pounds when most beech coffin smoothers are a little more than half that, I always despised how coffin smoothers can beat you up in less than ideal wood due to their light weight. The fact that the iron on this one lasts so poorly in fine smoothing gave me a reason to figure out some other way to use it, and I ended up learning more from it than I expected. Still dont like beech coffin smoothers in hardwoods.

My wife is on my case to trim my piles. I don't sell off much of anything without setting it up because most people don't know how to adjust a plane like this when it hasn't been used for decades. Once I set the planes up, I hate selling them, even though I've made my own.

I can't figure out how to post picture links from the imgur app, so I'll just share the gallery.

The joy of working with wooden planes

https://imgur.com/gallery/KgTW24k

This is work to come up with moulding stock. I've only been in the shop a half hour a day lately, and I haven't been getting much done because of it. Today was the same story.

Someone asked in the owt thread what the big deal is with cap irons when bu planes work so well. This is an example of it, cleaning up rough stock to be marked out and struck later.

Huge 10 to 14 thou shavings 2 1/8th wide taken at a lazy pace and smoother shavings about half that. Not even enough work to break a sweat, but I tried this in the past with bu planes and it was pure hell.

I made the cocobolo coffin smoother early on when trying to figure out how to make double iron planes well and the ih sorby iron in it is a little softer and not good at holding a fine edge, but it will take thicker shavings for eons, so I dedicated it to this. It is magic for machine planed wood, too. Chatter and evidence of any crushing or compression is gone in one or two passes with a near finished surface left behind.

For this kind of work in medium hardwoods, these types of planes are unequaled and this type of work will teach someone much faster methods of smoothing than taking tons of tiny shavings and getting sweated up. The cap iron makes it risk free.

The smoother even in this case will remove the sawmill marks from the rough side of the sticking in 8 strokes each side.

Keeping the thick shavings continuous and avoiding tearout keeps the plane so engaged that nothing but a round dog is needed at one end, and no constraints on the other.

As to why I made a big 2 1/4 inch smoother that is 4 pounds when most beech coffin smoothers are a little more than half that, I always despised how coffin smoothers can beat you up in less than ideal wood due to their light weight. The fact that the iron on this one lasts so poorly in fine smoothing gave me a reason to figure out some other way to use it, and I ended up learning more from it than I expected. Still dont like beech coffin smoothers in hardwoods.