I'm making my first table and have reached the point where I need to crosscut the legs and apron material to length prior to cutting mortises and tenons.

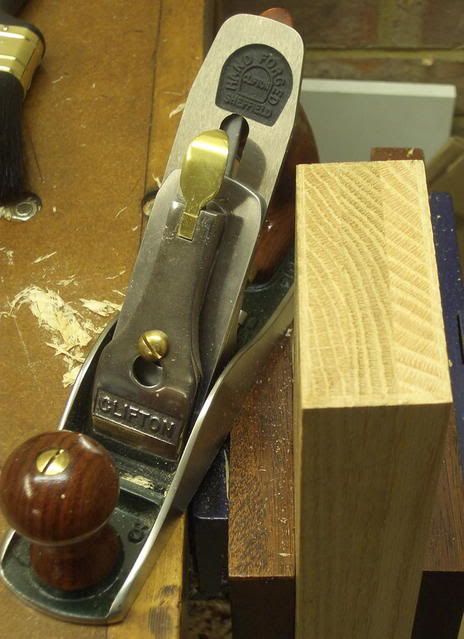

I'm wondering whether you would expect to make these sorts of crosscuts right at the line and work directly from the saw, or would you rather cut outside the line and use a shooting board to establish the final length. (Note that the leg stock is 44 mm thick and quite hard.)

I'm wondering whether you would expect to make these sorts of crosscuts right at the line and work directly from the saw, or would you rather cut outside the line and use a shooting board to establish the final length. (Note that the leg stock is 44 mm thick and quite hard.)