The best way to flatten the sole of a cast iron plane is to scrape it. Mark the high spots on a lapping plate with lapping fluid, and then scrape these away. Redo ... and redo ... and redo ... until there are no further high spots.

If you are not looking for precision (woodworking is not metal working, and all that), then sandpaper on a flat surface is the next best thing. Two points to keep in mind: (1) the substrate for the sandpaper must be flat, and the sandpaper must be flat on the flat substrate. There is no point in lapping on a sandpaper that is not flat. Keeping it flat is the job of a thin, even coat of

sprayed contact glue. Use a medium tack glue that can be scraped off when so needed. Holding the sandpaper down with water or anything that evaporates is just not good enough. Long lengths will curl at the edges, or lift as you push on them. (2) Technique is important. Lapping is not the same as sanding. If you try and sand the plane on the flat substrate, you will rock it and cause the sole to turn into a banana (that's how mine was). You have to push down on the plane as you simultaneously push it forward-and-back. Find a position where the load is spread along the whole length.

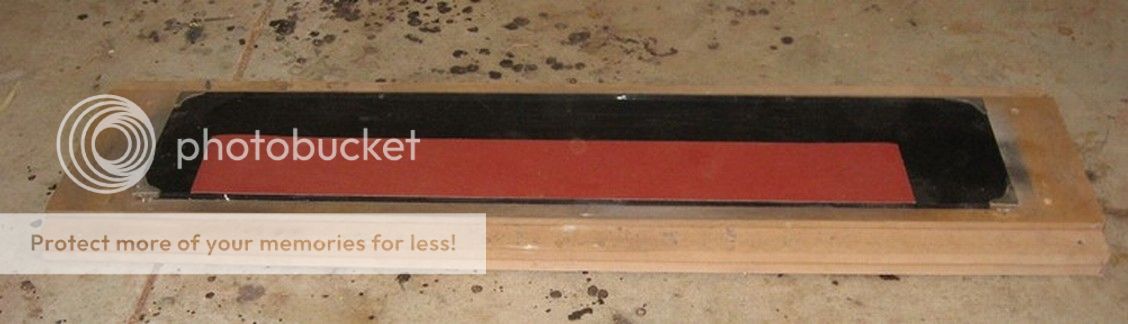

As I mentioned earlier, sandpaper for metal abrading is different from that used for wood. Charles gave it a name, emery cloth. That is one form (it comes in long roles). Another is A4 sheets on a fabric backing. That's the one I can get, in 100 grit. I cut it into sections and contact glue it to the substrate. It is flat, flat, flat.

You can re-use the contact glue on the substrate several times. No need to scrape it off.

Before I acquired the current substrate, a 3' x 4" section of 1/2" granite, I had a similar section of glass. I also experimented with belt sander belts (removing the join area). These work OK, but not as good as emery paper.

Here is the granite:

I simply rest it on the tablesaw when it is used. Afterwards it stands in a corner.

The paint brush is to brush away any swarf.

Glue it down to a flat substrate. Use the appropriate sandpaper. Watch your technique.

Regards from Perth

Derek