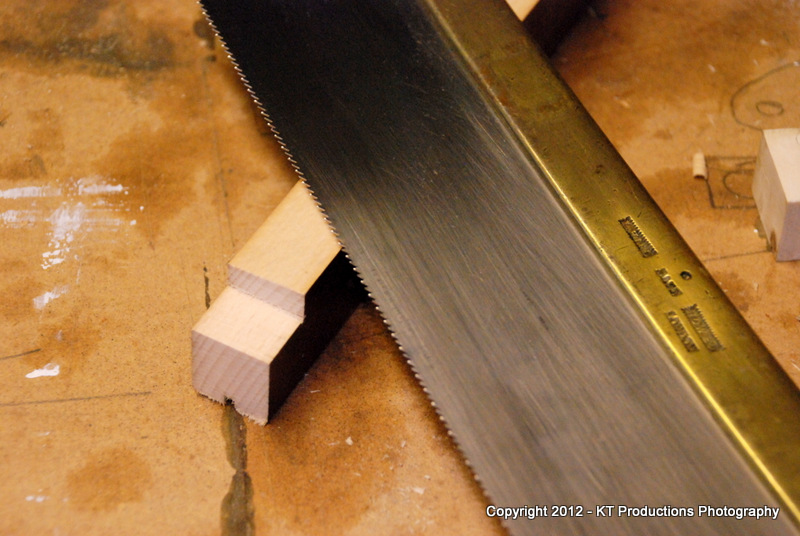

That looks to be a very satisfactory solution to the problem, and one that will give the best of two worlds - 19th century handle design and a nice, heavy brass back with modern blade steel quality (and a set of very even teeth - my compliments to The Dentist!). It shows that repair of older saws is not just possible, but practical.

I'll speculate a bit about blade steel from the mid 19th century, based on what Pedder's photographs show us. Quality control was difficult in those days because the equipment we have now to measure temperatures during heat treatment was not available, and the chemical analysis of steel samples was a slower affair - no mass spectrometers available in the steelworks of the day. Maybe this blade has fractured by the sawscrew holes, and at the teeth on setting, because the metal isn't quite as tempered as it should be; in other words, it's been hardened right out, but not tempered to a full spring temper. It's entirely possible that the teeth were originally not set at all (the carcase and dovetail saws in the Seaton chest are recorded as having no measurable set); as they are intended for relatively shallow cuts, a wide kerf is not so necessary as for a full tenon saw or handsaw. Fatigue cracks will happen sooner in harder steels. Just a theory, but plausible, I think.

It will be fun to hear how you get on with Harriette, Jimi. Do please let us know!