profchris

Established Member

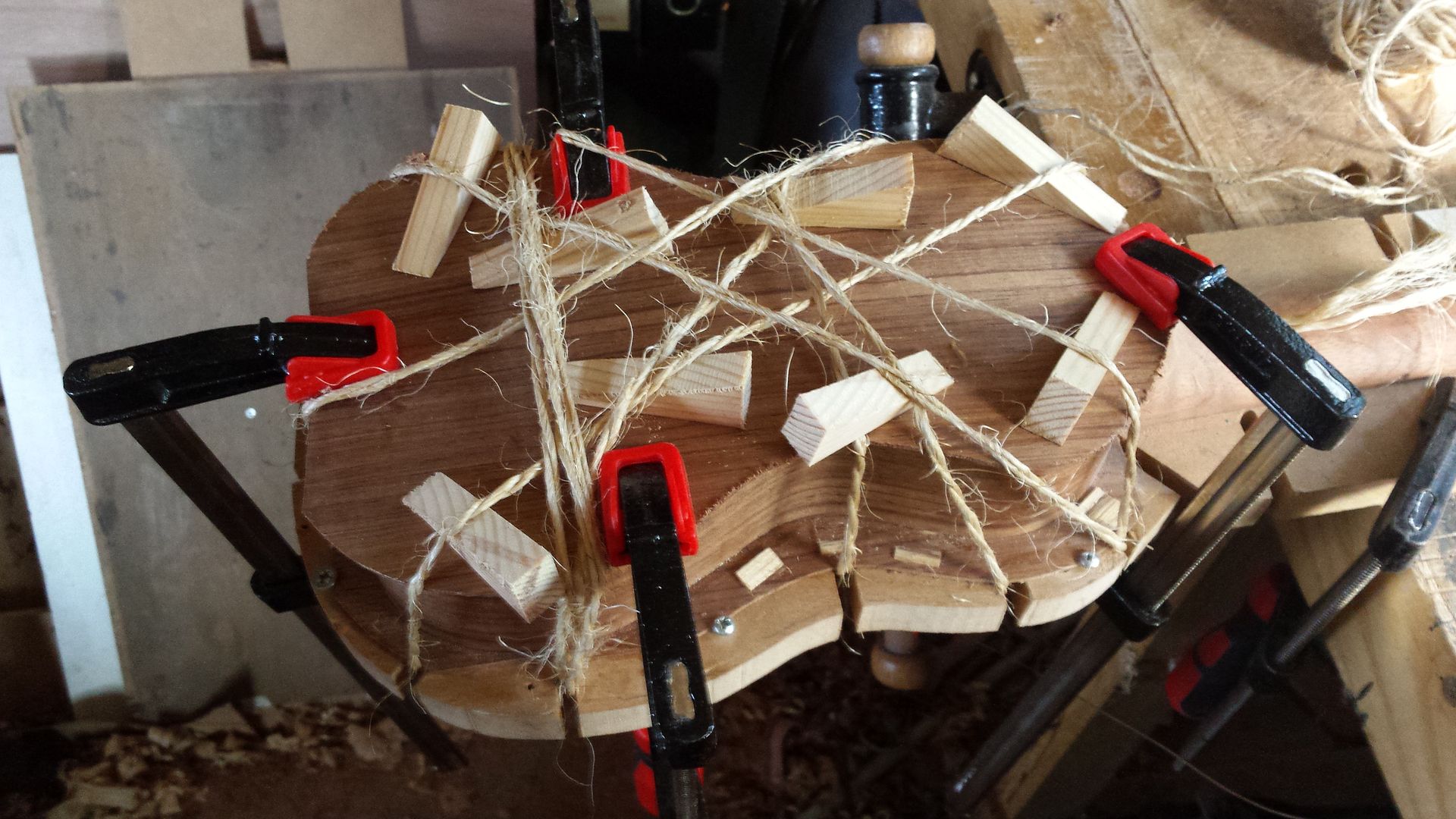

On Monday I completed the linings, including making pockets for the back brace to sit in.

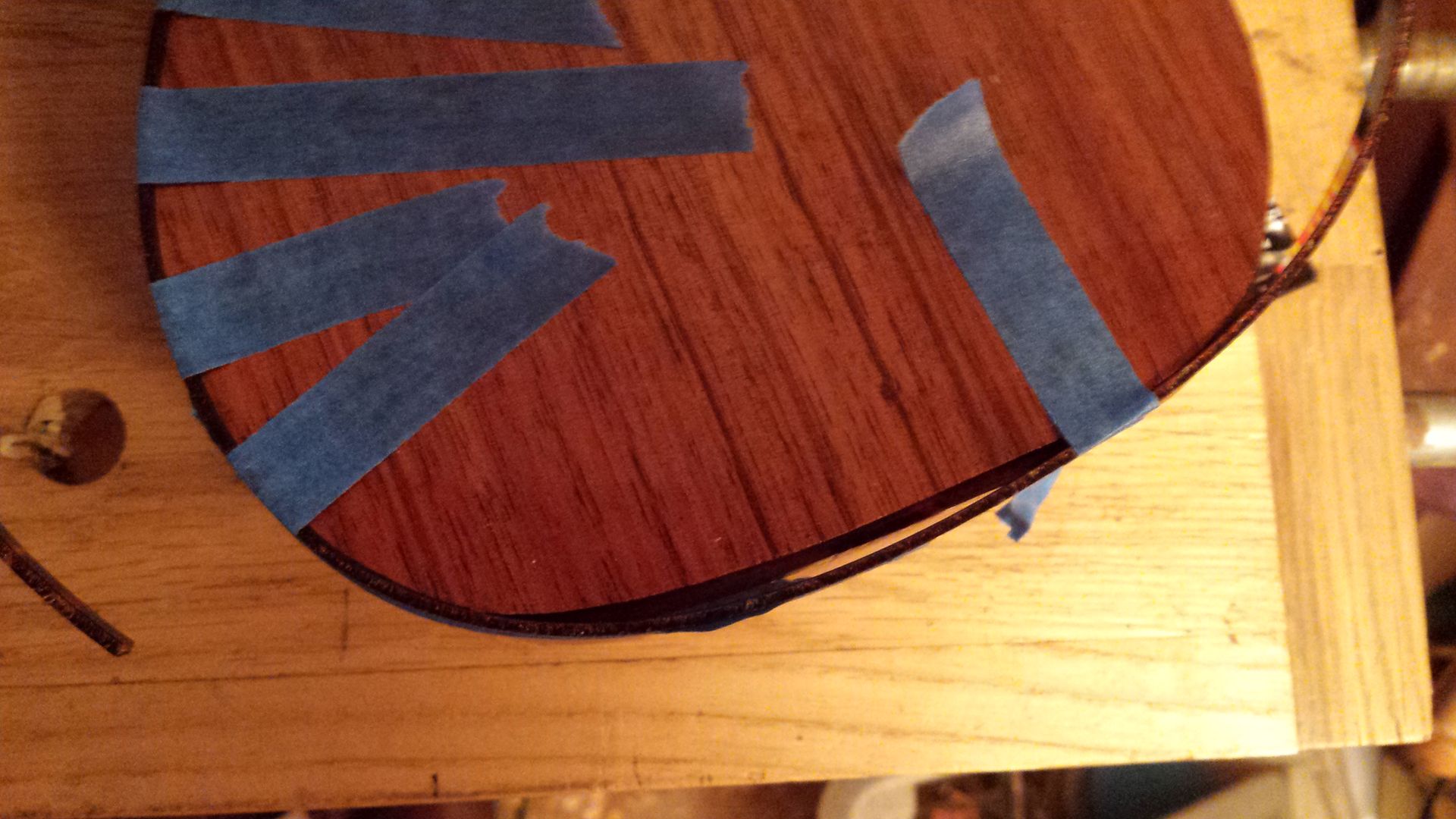

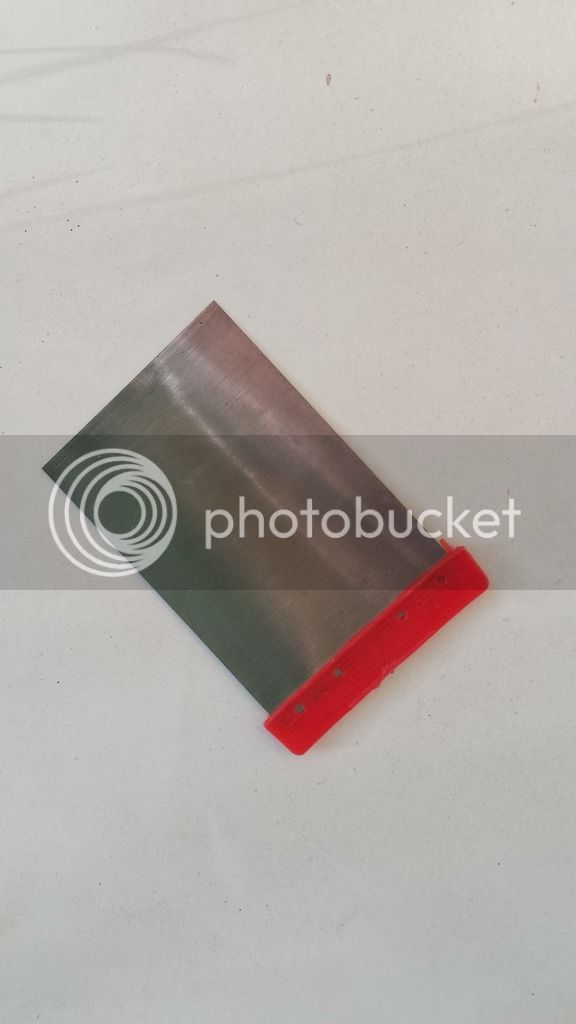

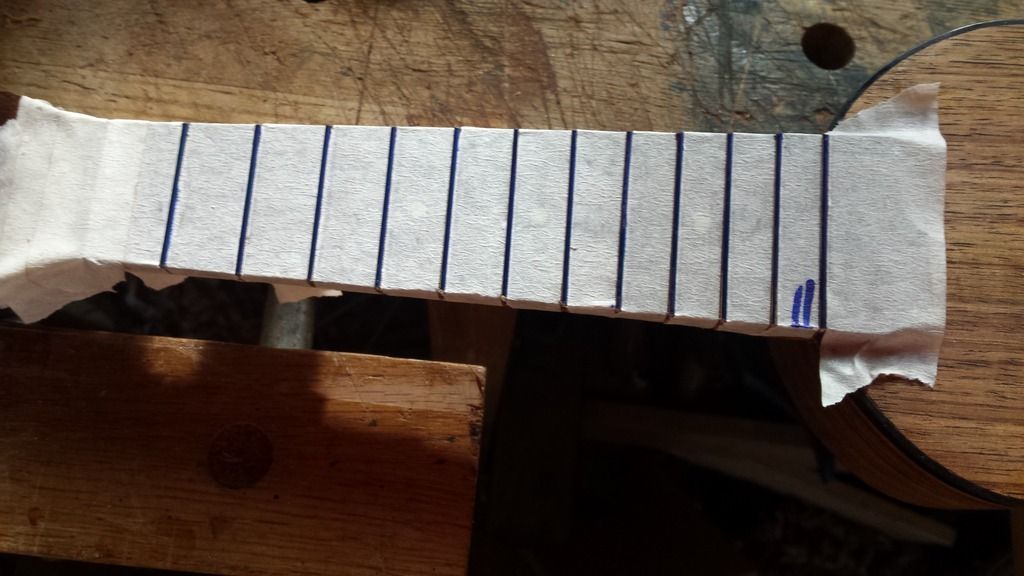

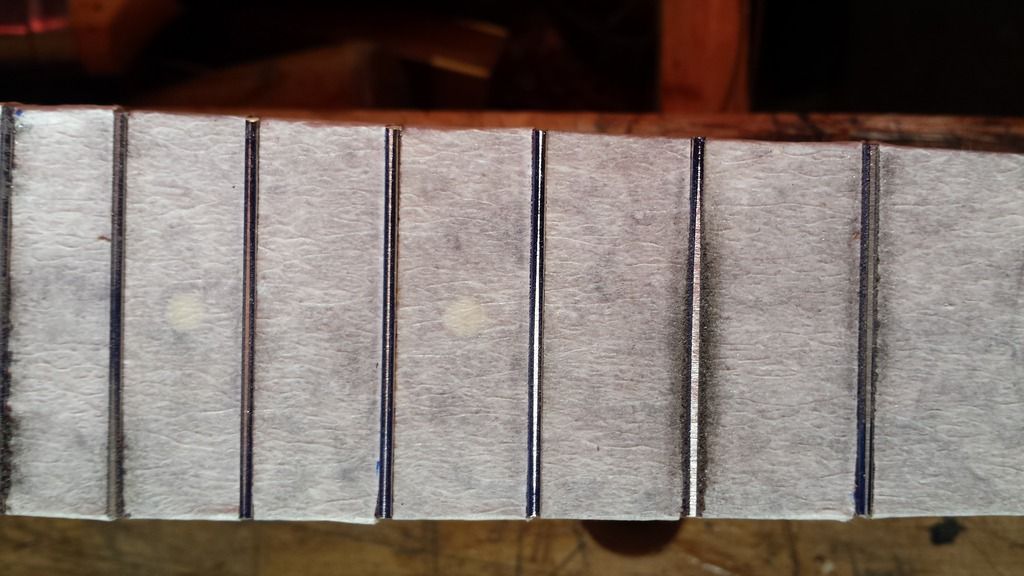

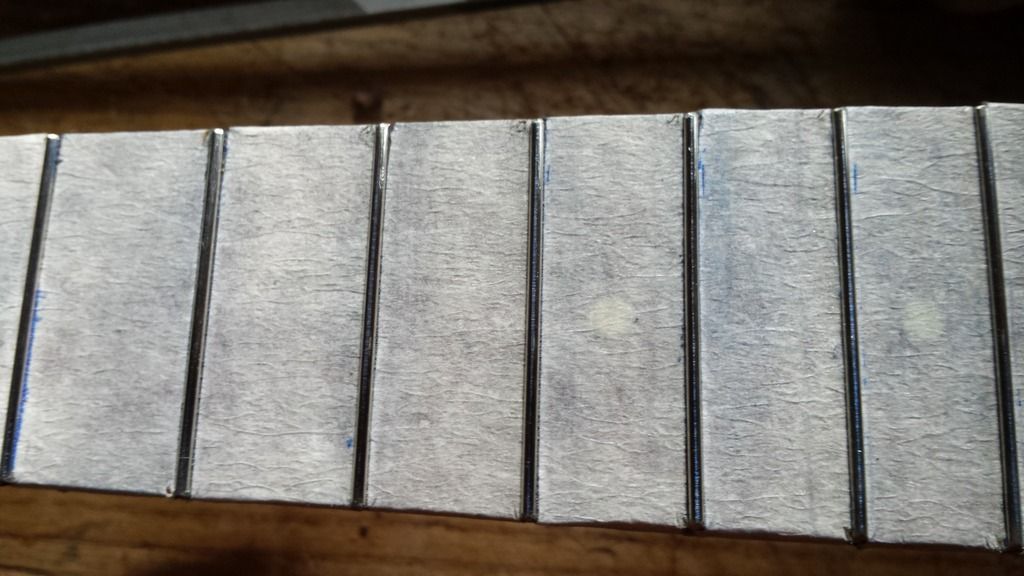

The linings are glued on a little proud of the sides and then taken down (initially with a plane, then by sanding) until they are EXACTLY the same height as the sides. How is "exactly" achieved?

Simples, my children. Rub pencil along the top surface of the sides and keep sanding until all the pencil is gone. Then you know your linings match the sides.

Once all the sanding is complete, it's a good time to take out that block screwed over the sound hole, as it won't be needed any more.

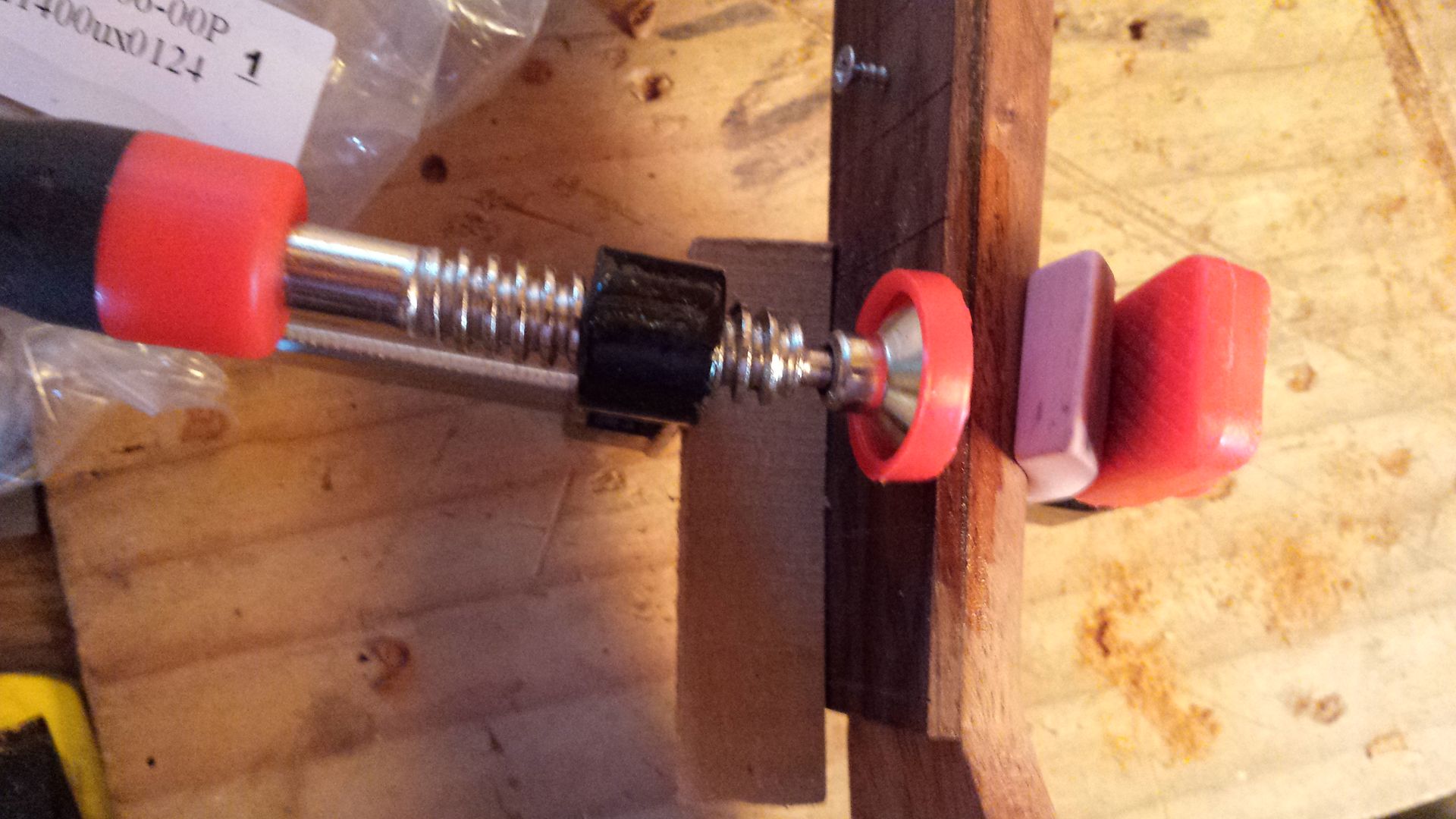

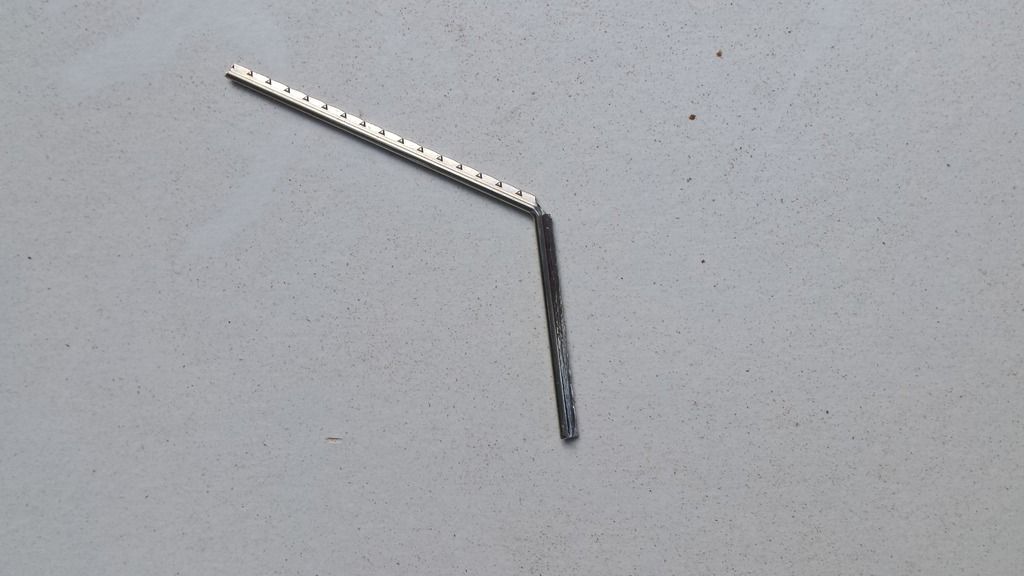

The back brace is made so it sits in the pockets and is gently curved, the centre being about 2mm higher than the sides.

There are two reasons for this. The first is aesthetic - you don't really see the tiny side-to-side curve, but it does just enough to make the back look even better. The second is more important - the back has to be glued firmly to the brace, but I find it easier to glue the brace to the sides now, and then when I put the back on I make sure it is also glued to the brace. The slight arch ensures that the brace pushes up into the back, so I'm confident there is contact all along the length of the brace when glueing.

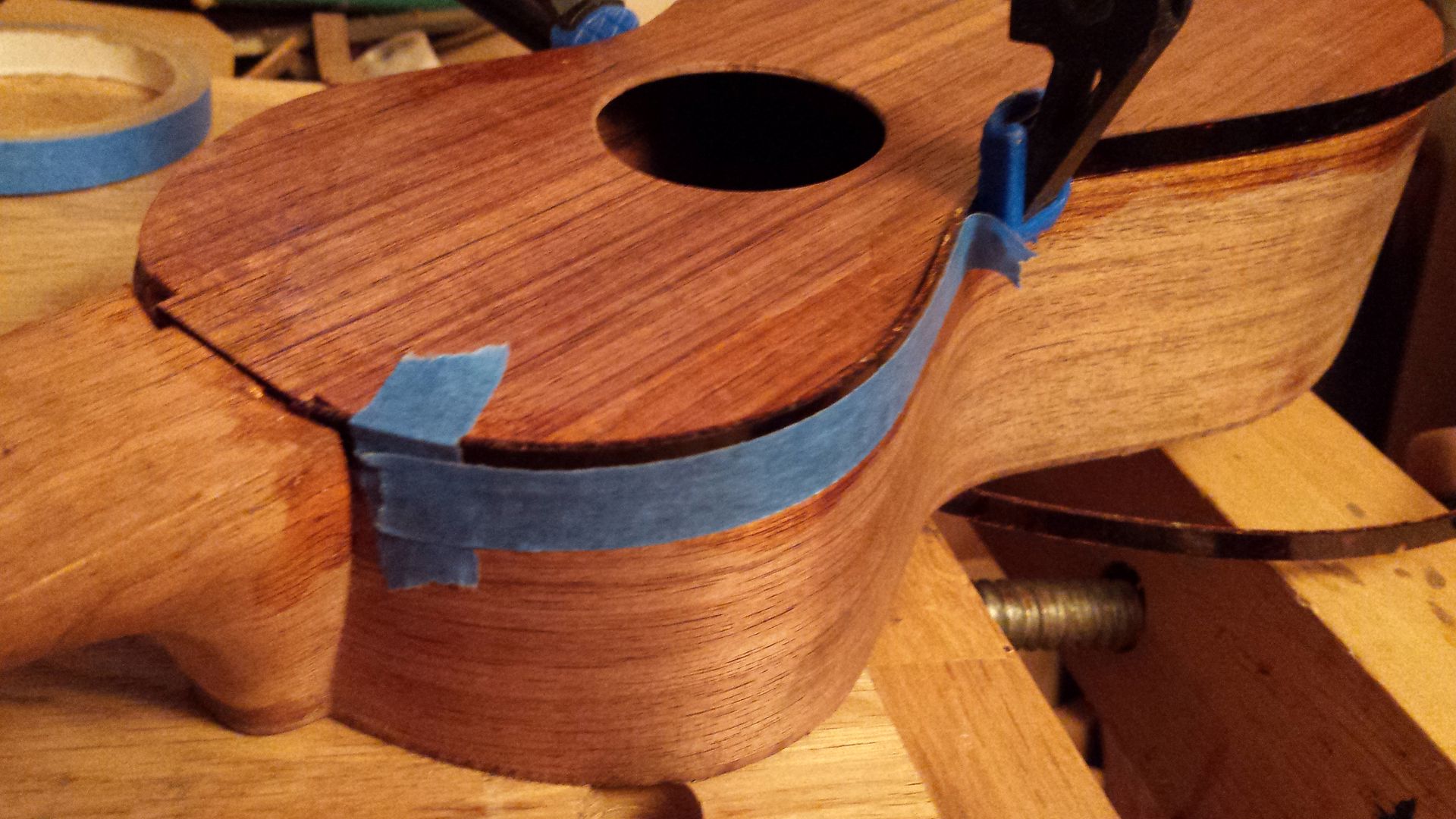

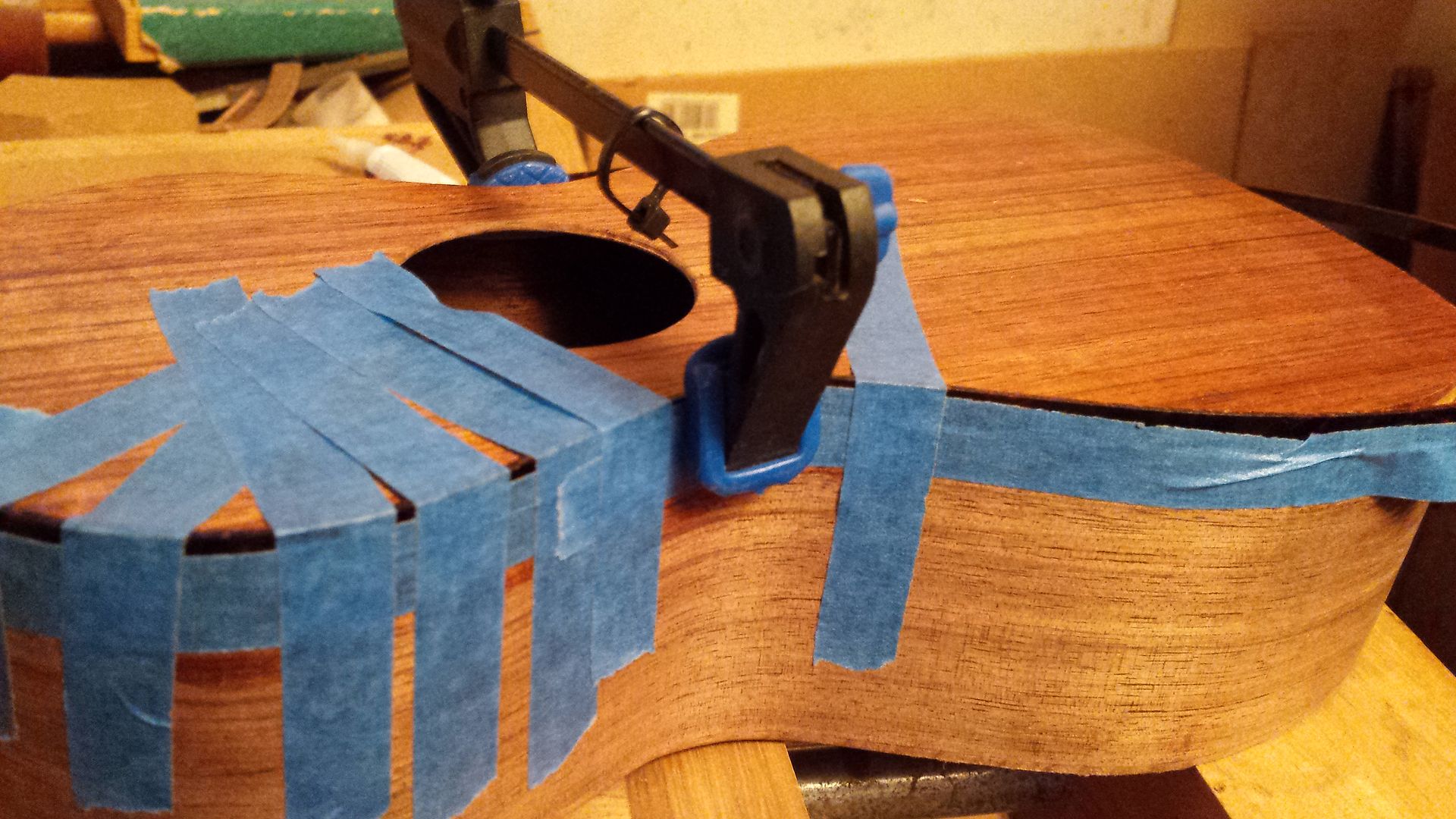

Finally for today I clamped the back in position and marked the shape on the underside. then I cut it about 1/4 inch bigger all round. I don't want a big overhang when glueing the back on, because if I put any pressure on the unsupported edge it might crack, so the less unsupported edge the better.

But as we shall see, by using hide glue I can rectify any glueing gaps between back and sides once the glue has dried, so I'm not going to be too desperate about clamping pressure there.

No glueing the back on today though, as evening is here and I have a long day in the office tomorrow. I will need to wait for a low humidity day to glue the back on, so everything is on pause until then.

The linings are glued on a little proud of the sides and then taken down (initially with a plane, then by sanding) until they are EXACTLY the same height as the sides. How is "exactly" achieved?

Simples, my children. Rub pencil along the top surface of the sides and keep sanding until all the pencil is gone. Then you know your linings match the sides.

Once all the sanding is complete, it's a good time to take out that block screwed over the sound hole, as it won't be needed any more.

The back brace is made so it sits in the pockets and is gently curved, the centre being about 2mm higher than the sides.

There are two reasons for this. The first is aesthetic - you don't really see the tiny side-to-side curve, but it does just enough to make the back look even better. The second is more important - the back has to be glued firmly to the brace, but I find it easier to glue the brace to the sides now, and then when I put the back on I make sure it is also glued to the brace. The slight arch ensures that the brace pushes up into the back, so I'm confident there is contact all along the length of the brace when glueing.

Finally for today I clamped the back in position and marked the shape on the underside. then I cut it about 1/4 inch bigger all round. I don't want a big overhang when glueing the back on, because if I put any pressure on the unsupported edge it might crack, so the less unsupported edge the better.

But as we shall see, by using hide glue I can rectify any glueing gaps between back and sides once the glue has dried, so I'm not going to be too desperate about clamping pressure there.

No glueing the back on today though, as evening is here and I have a long day in the office tomorrow. I will need to wait for a low humidity day to glue the back on, so everything is on pause until then.