profchris

Established Member

A friend's daughter Jenna (aged 10) won a set of Tasmanian Blackwood in the raffle at a ukulele festival, and very generously offered it to me as a present! Heavy negotiation ensued, and eventually I beat her up to me building the set as a uke for her. I also promised progress reports, and as I'm posting them on a uke board I thought they might be of interest to other woodworkers if I reproduced them here. Uke making is a strange combination of precision luthiery and improvised bodging.

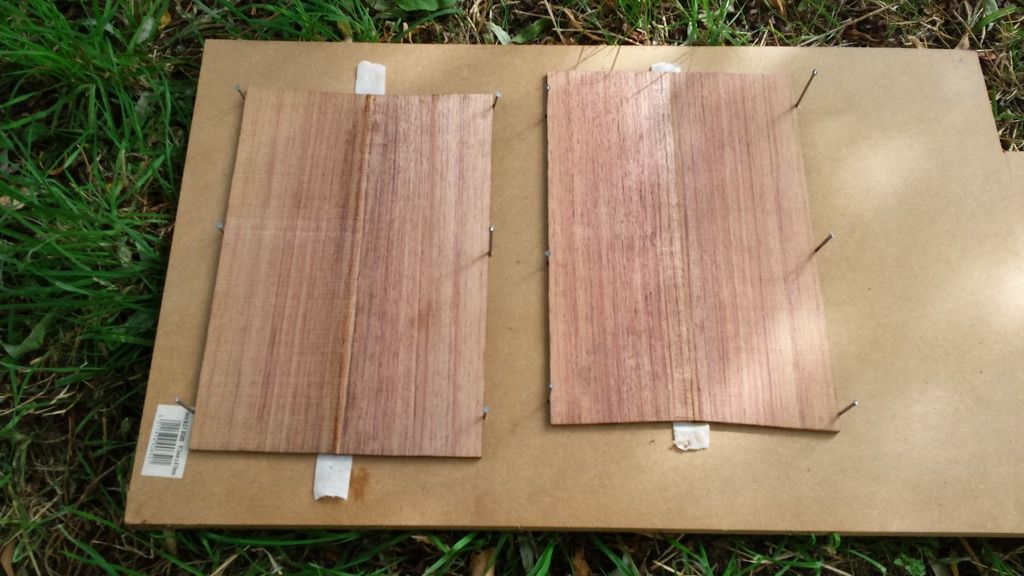

So, Jenna, I've made a start on the top and back. The wood is far too thick to make a ukulele, so I have to make it thinner. This picture shows your blackwood, and the thin bit is roughly how thick it needs to be.

Also top and back are each made of two pieces, so I need to glue them together before I start to make them thinner (which for some reason is called thicknessing!).

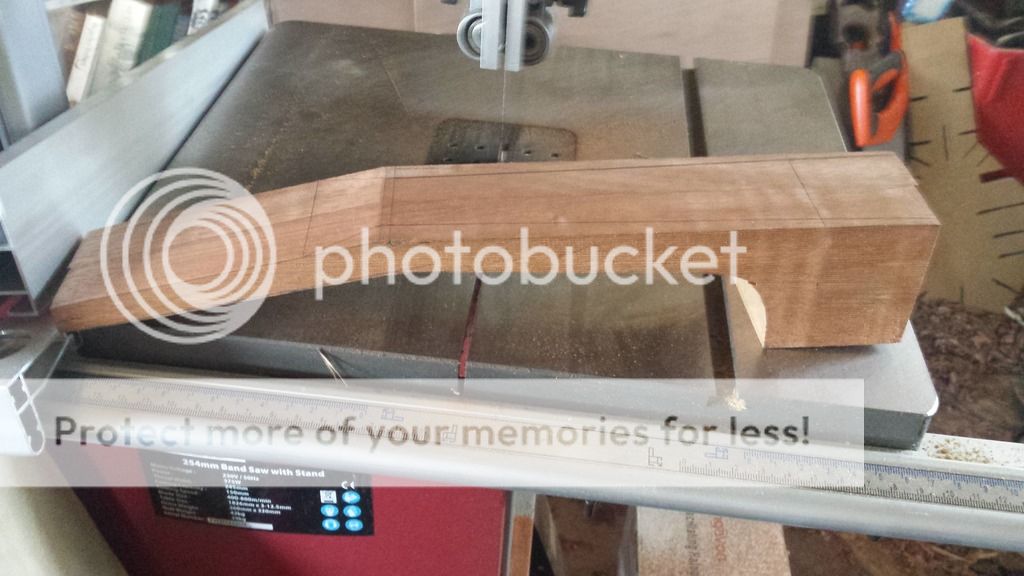

I need to get straight edges on both pieces to be glued, so I put them in a vice and get the edge to be joined roughly straight.

Then I take my very long plane:

And I use a cunning trick learnt from a friend (who learnt it from someone else) and clamp the plane upside down in the vice. Now I slide the two pieces across the plane to produce a perfect (I hope) joint.

The reason for doing both at the same time is that, even if I don't hold the wood absolutely upright, this will give me matching angles so that there are no gaps. We will find out once I start thicknessing!

So, Jenna, I've made a start on the top and back. The wood is far too thick to make a ukulele, so I have to make it thinner. This picture shows your blackwood, and the thin bit is roughly how thick it needs to be.

Also top and back are each made of two pieces, so I need to glue them together before I start to make them thinner (which for some reason is called thicknessing!).

I need to get straight edges on both pieces to be glued, so I put them in a vice and get the edge to be joined roughly straight.

Then I take my very long plane:

And I use a cunning trick learnt from a friend (who learnt it from someone else) and clamp the plane upside down in the vice. Now I slide the two pieces across the plane to produce a perfect (I hope) joint.

The reason for doing both at the same time is that, even if I don't hold the wood absolutely upright, this will give me matching angles so that there are no gaps. We will find out once I start thicknessing!