My point is that the heat input to the "sytem" is continuously fluctuating. A lump of stuff - closely thermally coupled with the workpiece - which has a high thermal inertia will smooth out these fluctuations in a way that helps to increase the average temperature of the workpiece over time (versus the equivalent setup without the added thermal mass)

[Note: On reflection, explaining my logic clearly here would be much better done with some diagrams, and/or a system of equations... But that's apparently not something my brain is willing to do for me at1am on a Tuesday morning. Sorry!]

So I'd agree that:

In no case could the thermal mass equilibrate to a temperature greater than the average temperature of the hottest element within the system (i.e. the heating element) because that would violate thermodynamic principles.

But, there's an additional factor to consider... Does some property of the thermal mass alter the modes of thermal transfer relative to the oven's design intent?

Ovens are designed for heat transfer via convection (be that natural or forced) to predominate, so the average temperature of the air as a heat transfer medium will act as a limit on the temperature an item in the oven can reach, exactly how you describe.

However many of the cheaper, naffer electric ovens I've used in my years as a connoseur of inexpensive rented houses, had elements which would get

far hotter than the desired air temperature when on, then just switch off for a bit.

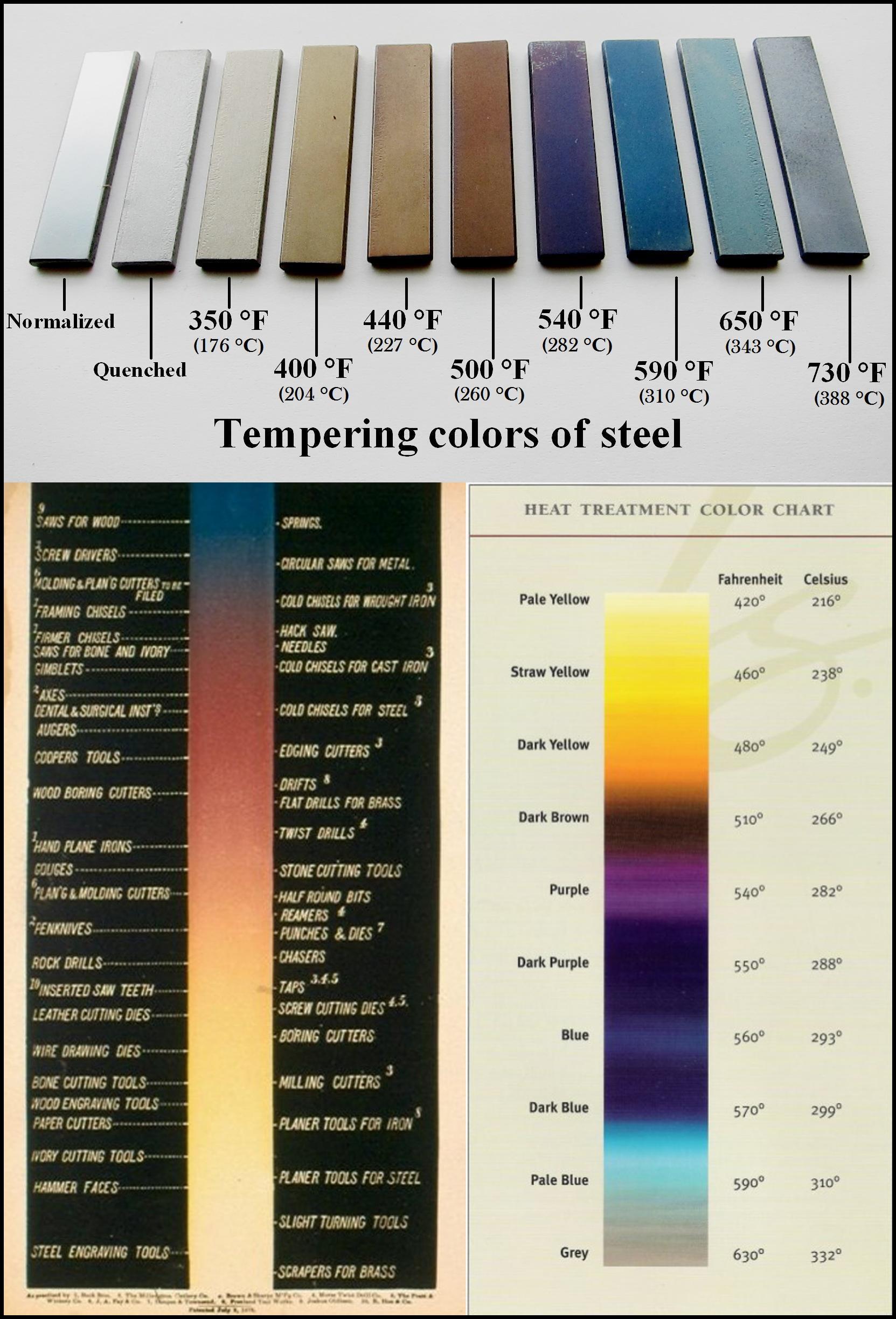

When I say far hotter I can be confident of this because the elements were visibly glowing, and incandescence generally begins to occur at no less than 525°C, that incandescence also means Radiative heat transfer is beginning to become relevant.

So... If the heating element is at a much higher temperature than the air, and you insert a thermal mass which has a substantially higher absorptivity than air it could equilibrate with the air temperature, and then continue to absorb energy via radiative thermal processes and reach a surface temperature greater than the air around it.

That hot (relative to the air) surface of the thermal mass would then begin to equilibrate with it's surroundings, and if it's a thermally conductive material, conduction would predominate so most of the thermal energy absorbed would be transferred into the interior of it, until it began to reach internal thermal equilibrium, meaning convective heat transfer to the air around it would start to predominate.

At which point the geometry of the thermal mass becomes important, because it is possible to have geometries in which the heat rate for radiative heat transfer into the thermal mass becomes equal to the heat rate of convective losses from the thermal mass, at an object temperature greater than the surrounding air temperature.

Only once the air temperature began to rise above it's setpoint as a result of that convective transfer from the thermal mass to the air, would the oven element turn off.

So in principle there's a plausible mechanism by which a thermal mass with the right geometry and material properties could reach a temperature higher than the average air temperature of the oven; provided the oven in question had a sufficiently crude control architecture to make the radiative heat transfer mechanism viable.