custard

Established Member

There was a post recently about edge jointing. I don't want to re-hash that, but one thing that didn't get much attention was edge jointing thin stock, and I'd class anything below 18mm or 3/4" as thin stock for edge jointing purposes.

It's worth emphasising that edge jointing, joining two narrow boards together to make a wider board, is the absolute primary woodworking joint. Unless you can do it confidently and consistently then your woodworking career is pretty much over before it's begun. Furthermore, it's one of the areas of woodworking where hand tool skills are still critical, edge jointing with machine planed, saw cut, or router formed edges will always be inferior to those made with a hand plane. In fact if you apprentice as a cabinet maker, or sign up on a furniture making course, it's almost certain that the syllabus will start as follows. Step one, fettle and sharpen a hand plane. Step two, plane a board so all six faces are square and true. Step three, edge joint two or three boards together and make something simple like a chopping board. The real lesson to take from that is that you can't seriously begin to even learn about furniture making until you're reasonably proficient at edge jointing by hand.

Edge jointing moderately thick boards is the sensible place to start. A typical cabinet or side table top will usually be about 21/22mm thick, or about 7/8". And this is what a 5 1/2 plane looks like balanced on a 21mm thick board.

Anything in the range 18-25mm thick will let the plane balance nicely, so is fine for your first attempts.

But once you advance in furniture making you'll find that you frequently need to edge joint thinner stock. And then things start to get progressively trickier.

This is what a 5 1/2 plane looks like balanced on the edge of a 12mm thick drawer side.

This is pretty much as thin as I'd like to go for edge jointing with the board held vertically in a vice. Sure I can plane a much thinner board smooth, but edge jointing demands planing it smooth, straight and true. And despite being a full time furniture maker with many years experience under my belt, this is the limit of my own personal skill. For the average hobbyist I'd suggest 18mm is a sensible minimum. The problem is that the board starts to flex as it gets thinner, and so the plane begins to wobble, which means you're introducing wind to the edge, also it's probably going to be complex wind that will go one way and then the other and then switch back again.

Even if you think you're skilled enough to go thinner than 12mm with the workpiece held in a vice, the board thicknesses commonly used in cabinet making will still catch you out before long.

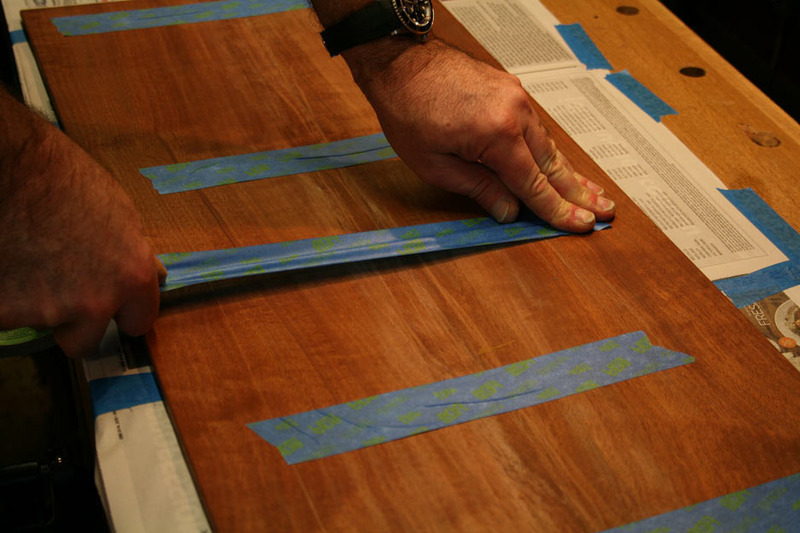

This is an edge jointed, 8mm thick, "standard" drawer bottom in Cedar of Lebanon,

And this is a 5 1/2 plane balanced on that 8mm edge, that's now really looking unstable

And the problem doesn't stop there. At some point you'll certainly need 6mm or 4mm thick stuff for your furniture. Until eventually you'll be faced with edge jointing 2mm thick saw cut veneers!

And top end furniture makers usually edge joint together even 0.6mm thick commercial veneers as a matter of course!

That's as many photos as will go in one post, so I'll follow on with a separate post on practical solutions to this problem.

It's worth emphasising that edge jointing, joining two narrow boards together to make a wider board, is the absolute primary woodworking joint. Unless you can do it confidently and consistently then your woodworking career is pretty much over before it's begun. Furthermore, it's one of the areas of woodworking where hand tool skills are still critical, edge jointing with machine planed, saw cut, or router formed edges will always be inferior to those made with a hand plane. In fact if you apprentice as a cabinet maker, or sign up on a furniture making course, it's almost certain that the syllabus will start as follows. Step one, fettle and sharpen a hand plane. Step two, plane a board so all six faces are square and true. Step three, edge joint two or three boards together and make something simple like a chopping board. The real lesson to take from that is that you can't seriously begin to even learn about furniture making until you're reasonably proficient at edge jointing by hand.

Edge jointing moderately thick boards is the sensible place to start. A typical cabinet or side table top will usually be about 21/22mm thick, or about 7/8". And this is what a 5 1/2 plane looks like balanced on a 21mm thick board.

Anything in the range 18-25mm thick will let the plane balance nicely, so is fine for your first attempts.

But once you advance in furniture making you'll find that you frequently need to edge joint thinner stock. And then things start to get progressively trickier.

This is what a 5 1/2 plane looks like balanced on the edge of a 12mm thick drawer side.

This is pretty much as thin as I'd like to go for edge jointing with the board held vertically in a vice. Sure I can plane a much thinner board smooth, but edge jointing demands planing it smooth, straight and true. And despite being a full time furniture maker with many years experience under my belt, this is the limit of my own personal skill. For the average hobbyist I'd suggest 18mm is a sensible minimum. The problem is that the board starts to flex as it gets thinner, and so the plane begins to wobble, which means you're introducing wind to the edge, also it's probably going to be complex wind that will go one way and then the other and then switch back again.

Even if you think you're skilled enough to go thinner than 12mm with the workpiece held in a vice, the board thicknesses commonly used in cabinet making will still catch you out before long.

This is an edge jointed, 8mm thick, "standard" drawer bottom in Cedar of Lebanon,

And this is a 5 1/2 plane balanced on that 8mm edge, that's now really looking unstable

And the problem doesn't stop there. At some point you'll certainly need 6mm or 4mm thick stuff for your furniture. Until eventually you'll be faced with edge jointing 2mm thick saw cut veneers!

And top end furniture makers usually edge joint together even 0.6mm thick commercial veneers as a matter of course!

That's as many photos as will go in one post, so I'll follow on with a separate post on practical solutions to this problem.