By the time I got to doing a controlled test with end grain, I was using only two irons. V11 separated itself from everything except M4, and M4 had a wrist-aching amount of planing resistance, so it's not something I'd make an iron from with V11's base metal available as bar stock.

FWIW, I only have one actual V11 iron, though I've had 3 now. The planes the other two came in are sold, and their irons went with them.

One of those planes was a LV shoot plane. I wanted to compare the shoot plane to a skew infill shooter I was building. I didn't, and still haven't seen much difference in most woods between O1 and V11 on end grain. V11 is good, but only slightly better than *similar hardness* O1.

I made the O1 iron in this test, tested it against a hock later (it lasted about 5% longer footage-wise than the hock, which means the two are probably a statistical dead heat). I don't have a hock iron in #4, so a choice to use it in a different plane instead of my own make of iron would've been less reliable.

Anyway, on a 14 inch wide cherry board, planing end grain with a #4, the footage results for V11 vs. O1 are:

O1 - 1013 feet planed

V11 - 1088 feet planed

(the last third of each of these was wrist breaking, but the irons continued to cut so I continued to plane with them until they started skipping out of the cut. V11 again was slicker through the cut and less effort overall, but it's planing endgrain, so no heavy cut is easy).

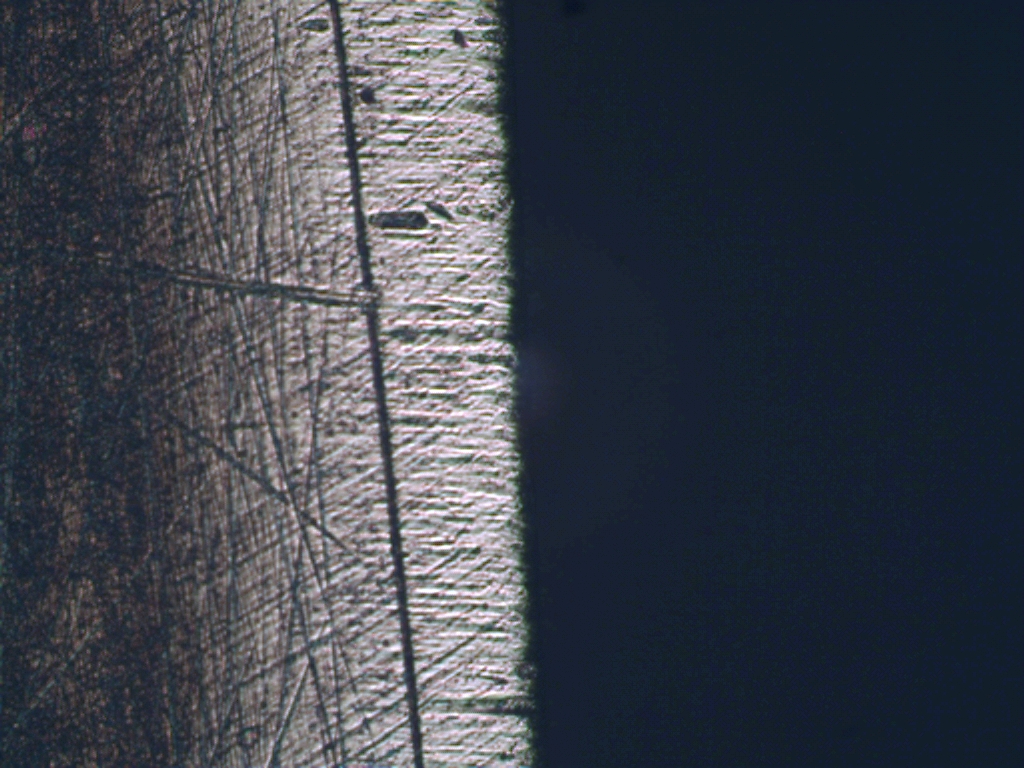

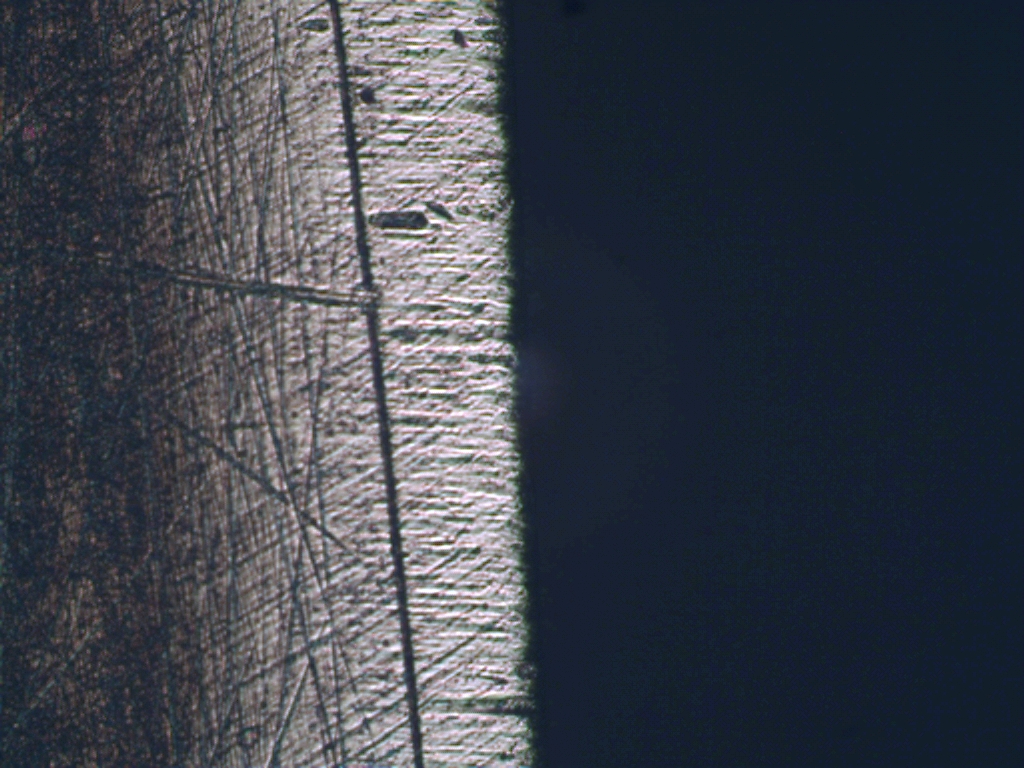

Noticeably harder on edges - O1 (at the end of the test):

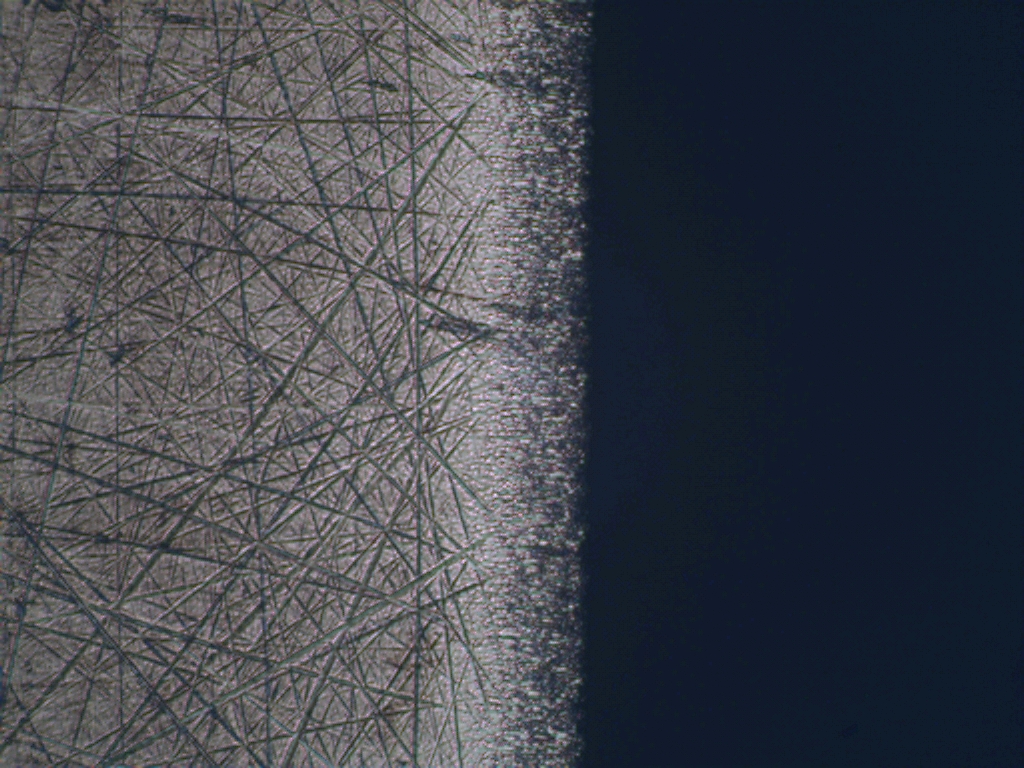

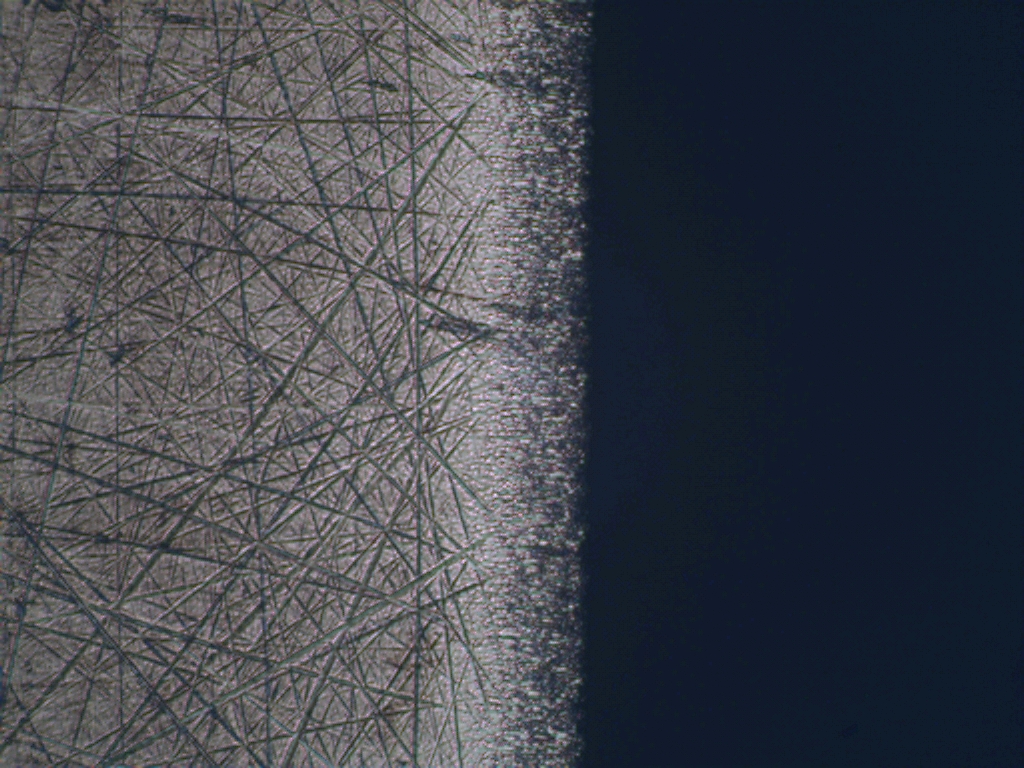

And V11 at the end:

Some of you won't believe that you can plane a thousand feet in endgrain with a smoothing plane (cherry in this case, not beech - beech end grain is much more resistant to planing).

This wood was in the vise upright. What you won't notice when you're planing is that just the exercise of pushing on the handle and laying your hands on your plane somewhere applies quite a bit of downforce. You lose this when you lay a plane on its side. It's far more efficient to plane larger panels on edge and end grain with the work upright than it is to shoot the edges, and sharpening can be less frequent.

How would a stanley or record laminated iron fare against the O1 iron in this test? Less well. I'd guess 2/3rds as long to 80%. The only vintage iron I tested in anything was Ward in a norris #2. It wore evenly but didn't last as long as O1. Hardness of the ward was similar, perhaps a point or two less hard than the house O1 iron.

Wax often if planing end grain on a large panel in the vise. The newer the plane and more perfect the sole, the more valuable wax becomes. the LN bronze used for all of these tests is a very high friction plane without wax. Almost unbearable. Less perfect older planes tend to have a smaller gap between waxed and unwaxed resistance. New premium cast iron planes are marginally less sticky than the bronze, but more friction than vintage planes. Wax equalizes them, but you have to remember to keep applying it

FWIW, I only have one actual V11 iron, though I've had 3 now. The planes the other two came in are sold, and their irons went with them.

One of those planes was a LV shoot plane. I wanted to compare the shoot plane to a skew infill shooter I was building. I didn't, and still haven't seen much difference in most woods between O1 and V11 on end grain. V11 is good, but only slightly better than *similar hardness* O1.

I made the O1 iron in this test, tested it against a hock later (it lasted about 5% longer footage-wise than the hock, which means the two are probably a statistical dead heat). I don't have a hock iron in #4, so a choice to use it in a different plane instead of my own make of iron would've been less reliable.

Anyway, on a 14 inch wide cherry board, planing end grain with a #4, the footage results for V11 vs. O1 are:

O1 - 1013 feet planed

V11 - 1088 feet planed

(the last third of each of these was wrist breaking, but the irons continued to cut so I continued to plane with them until they started skipping out of the cut. V11 again was slicker through the cut and less effort overall, but it's planing endgrain, so no heavy cut is easy).

Noticeably harder on edges - O1 (at the end of the test):

And V11 at the end:

Some of you won't believe that you can plane a thousand feet in endgrain with a smoothing plane (cherry in this case, not beech - beech end grain is much more resistant to planing).

This wood was in the vise upright. What you won't notice when you're planing is that just the exercise of pushing on the handle and laying your hands on your plane somewhere applies quite a bit of downforce. You lose this when you lay a plane on its side. It's far more efficient to plane larger panels on edge and end grain with the work upright than it is to shoot the edges, and sharpening can be less frequent.

How would a stanley or record laminated iron fare against the O1 iron in this test? Less well. I'd guess 2/3rds as long to 80%. The only vintage iron I tested in anything was Ward in a norris #2. It wore evenly but didn't last as long as O1. Hardness of the ward was similar, perhaps a point or two less hard than the house O1 iron.

Wax often if planing end grain on a large panel in the vise. The newer the plane and more perfect the sole, the more valuable wax becomes. the LN bronze used for all of these tests is a very high friction plane without wax. Almost unbearable. Less perfect older planes tend to have a smaller gap between waxed and unwaxed resistance. New premium cast iron planes are marginally less sticky than the bronze, but more friction than vintage planes. Wax equalizes them, but you have to remember to keep applying it