Derek Cohen (Perth Oz)

Established Member

Part 1 - design and construction

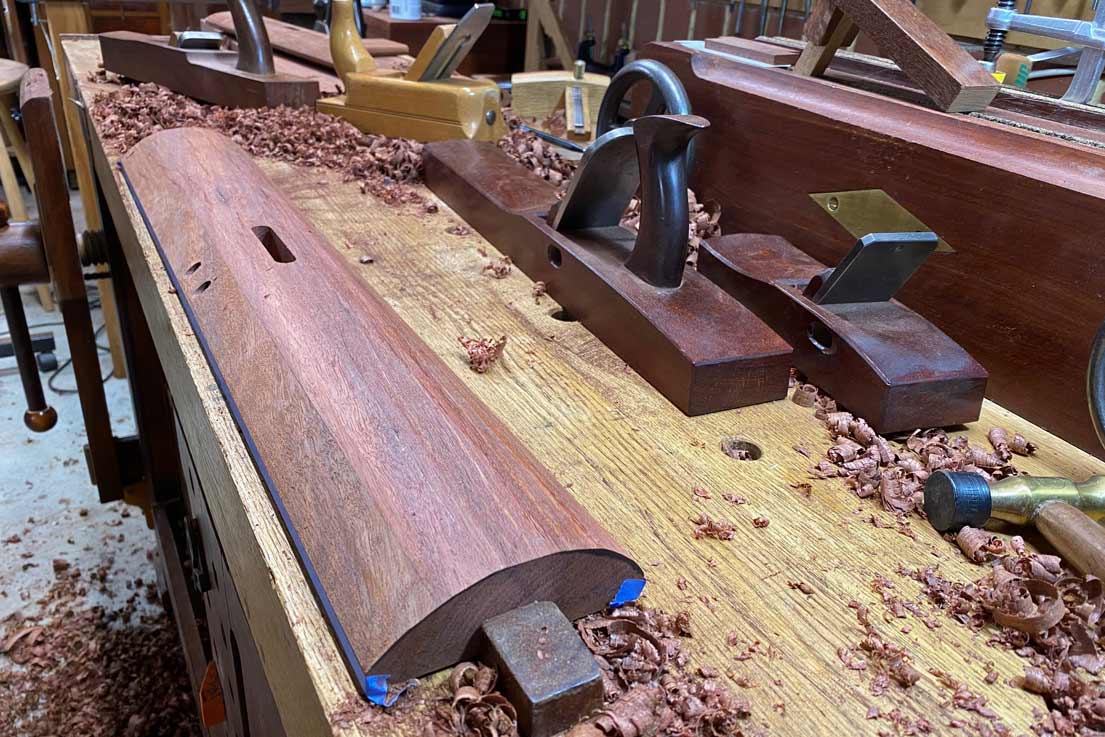

The brief is to build an 8-seater dining table to replace our existing 6-seater. We will retain the 6 vintage bentwood chairs, and I recently completed 2 (DC 09) chairs for use as carvers. Our taste in furniture runs towards the minimalistic, the clean lines of mid century designs from the 1930s, gentle curves. What is needed in a design is a way to link and blend the chairs with the table. In part this will be aided by the wood used for the table top: both the carvers and the top are Rock Maple. Another element will be the presence of the curves in the chairs, which will extend to the table.

The old table was 200 years old and came with us from from South Africa when we moved to Sydney 40 years ago. The top was Yellow Wood (which resembles an aged Maple), and the legs were Stinkwood (a dark wood). The latter will be represented by Jarrah.

Another need for the new table is that is must be knock-down. We plan to move home in about 18 months, downsizing when I retire. The new home is similar in size, but with less garden to manage. Being knock-down cannot impose on the design, and cannot impact on the rigidity of the construction. Today I will show you what I came up with.

The old table was 1350mm (53") long, 850mm (33 1/5") wide and 775mm (30 1/2") high.

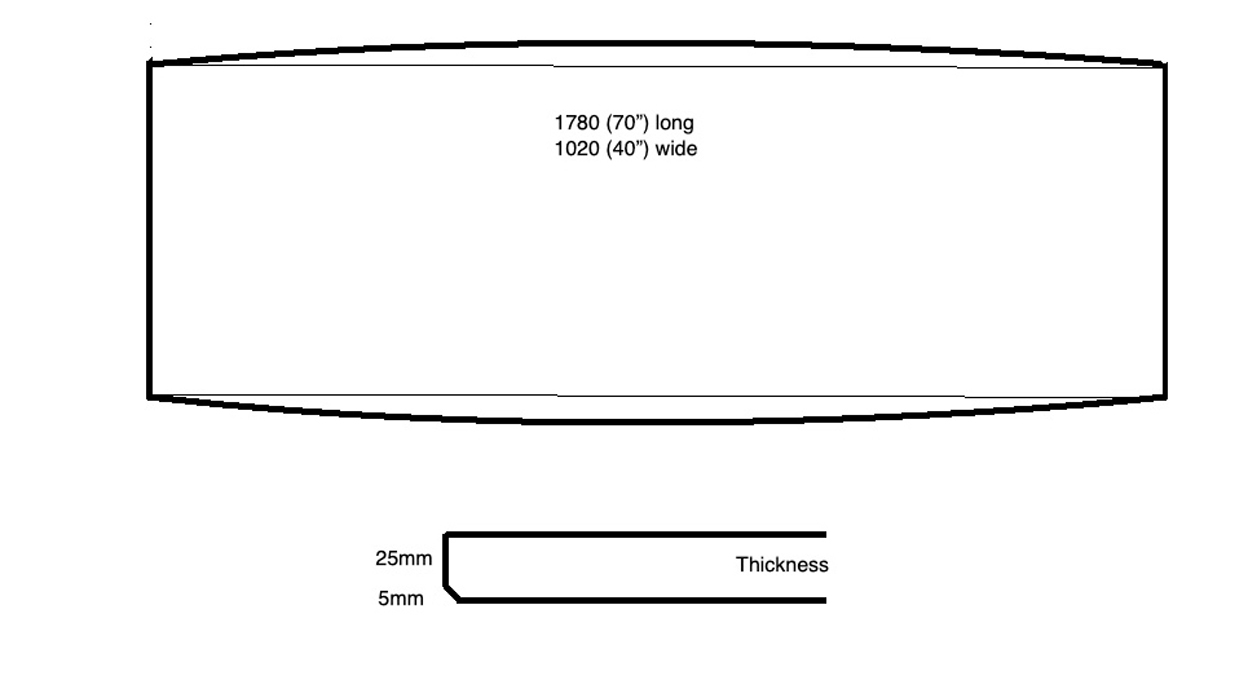

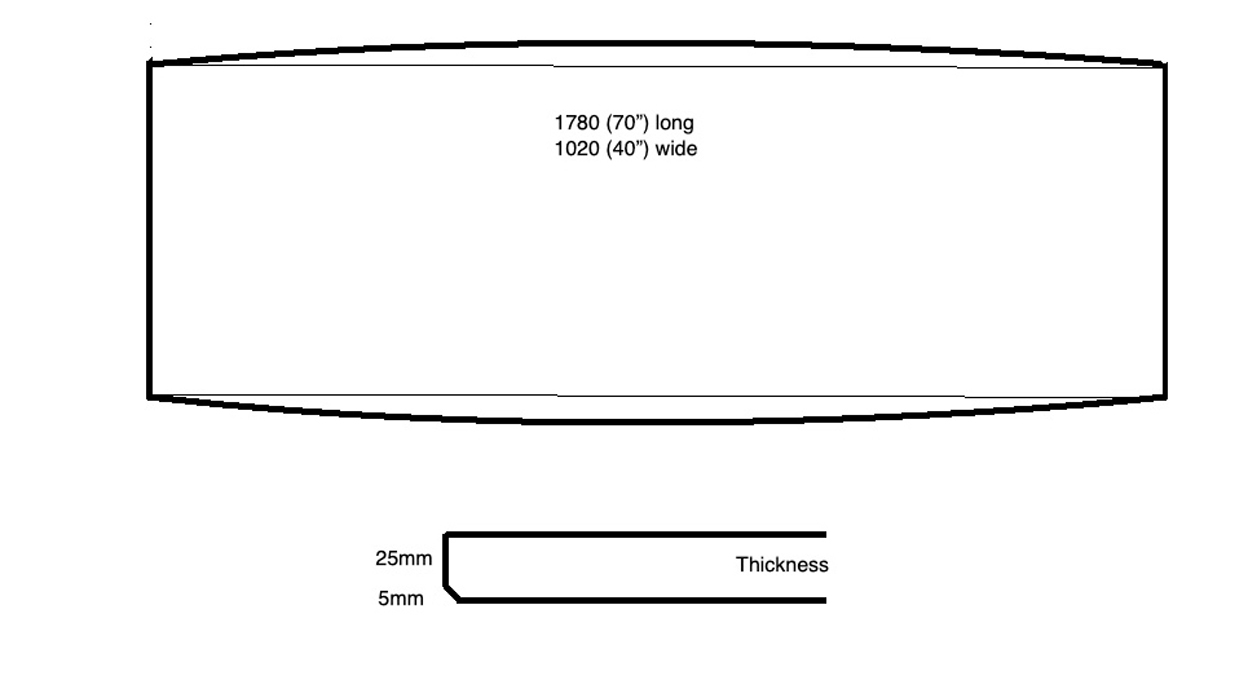

The new table will be 1780mm (70") long, 1020mm wide (40"), and 760mm (30") high.

I found a photo of a table with similar proportions. This table has rectangular legs, but its silhouette creates the illusion that the legs are round, which will be the case in this build.

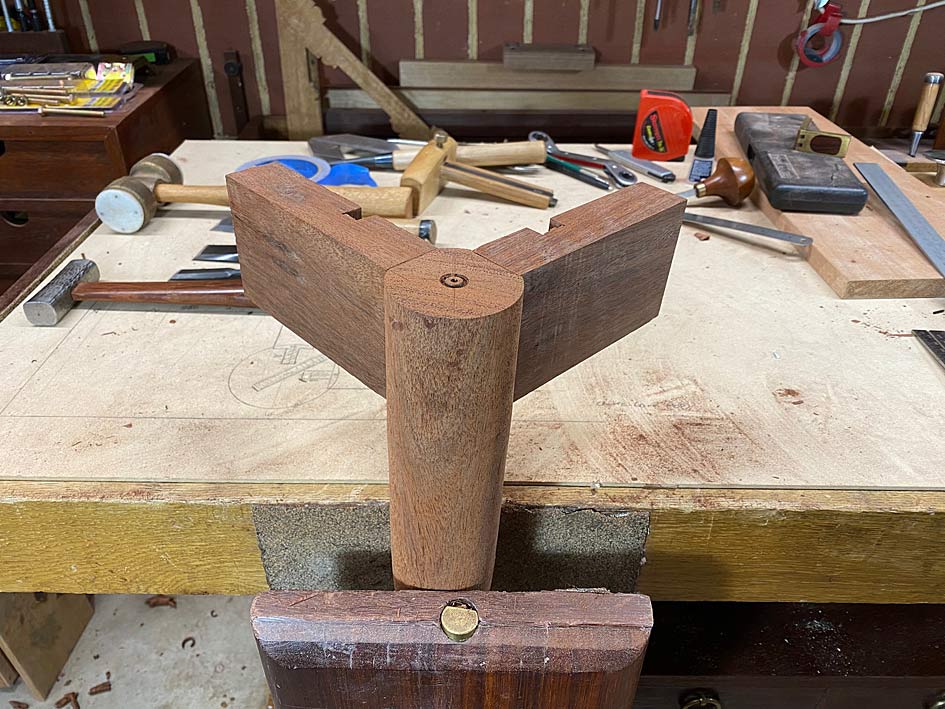

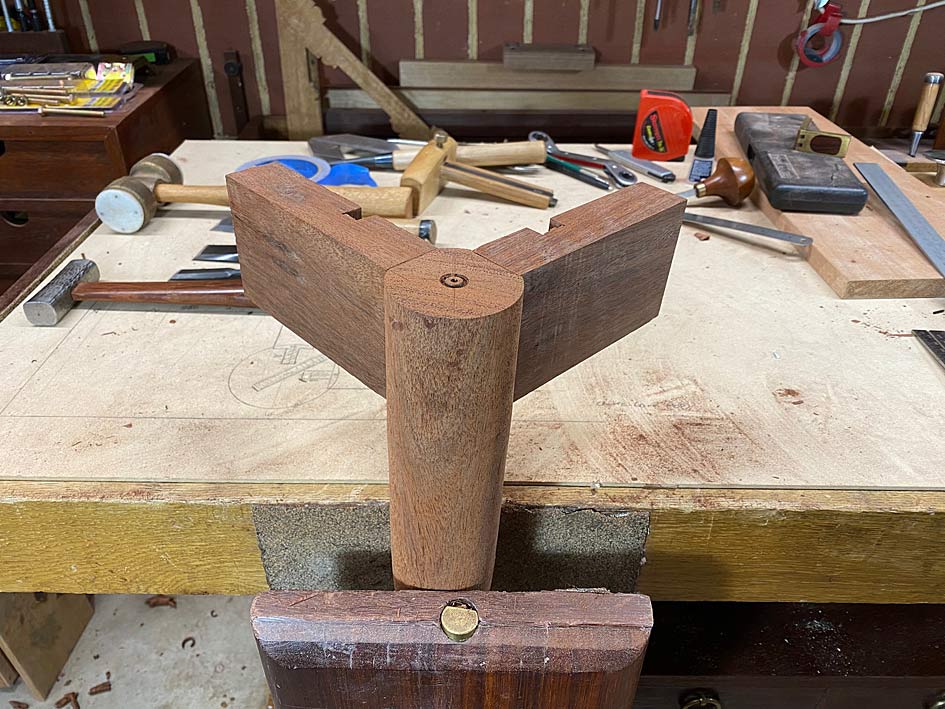

When I began test-building the leg-rail build, the legs were to have a 75mm (3") diameter with a rail of similar width. The legs ended up too chunky, and were subsequently reduced to 60mm (2 3/8") diameter. I am considering reducing the rails to 60mm as well (they are 75mm in the photos), but am concerned about a drop in rigidity. Having stated this, the rails are 30mm wide, Jarrah, and this is quite substantial.

So to the construction ...

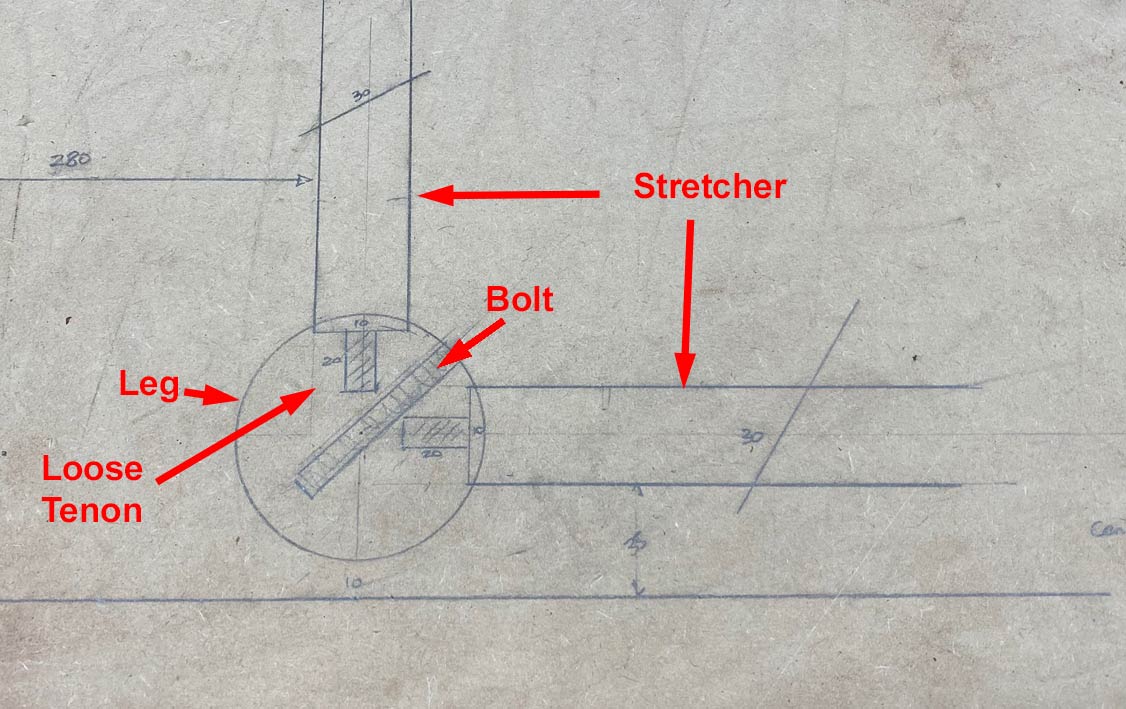

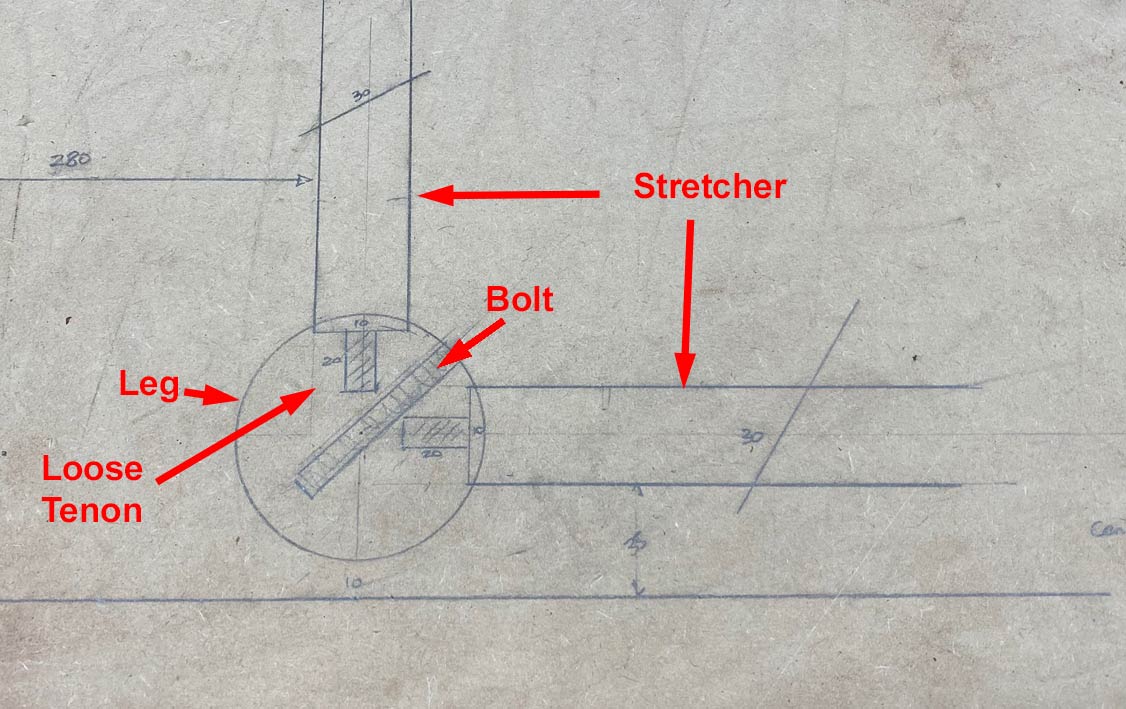

The rails (or stretcher) are connected to the legs with loose tenons. The tenons are glued to the end of the rails, but left unglued when connected to the legs.

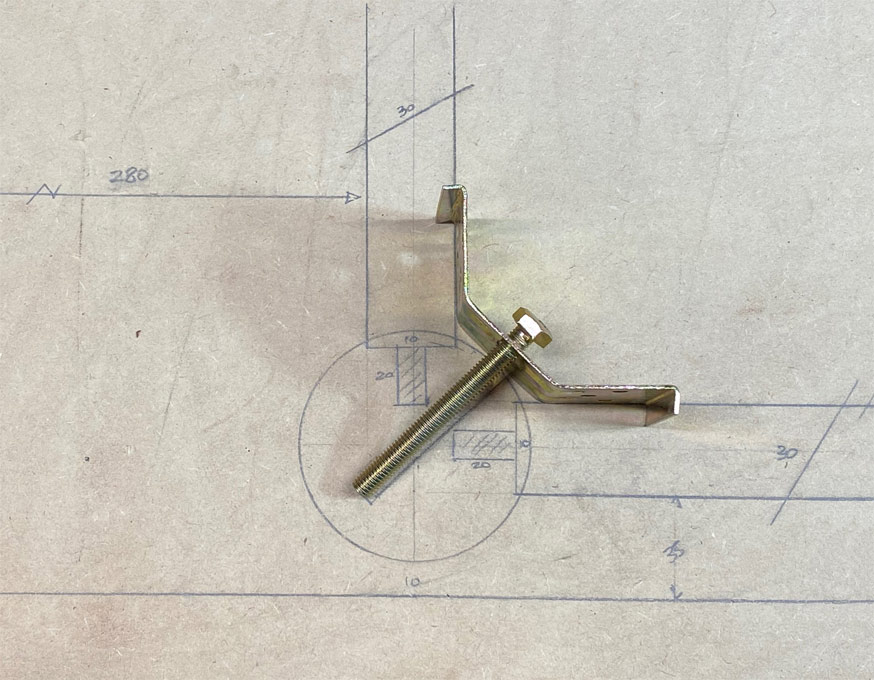

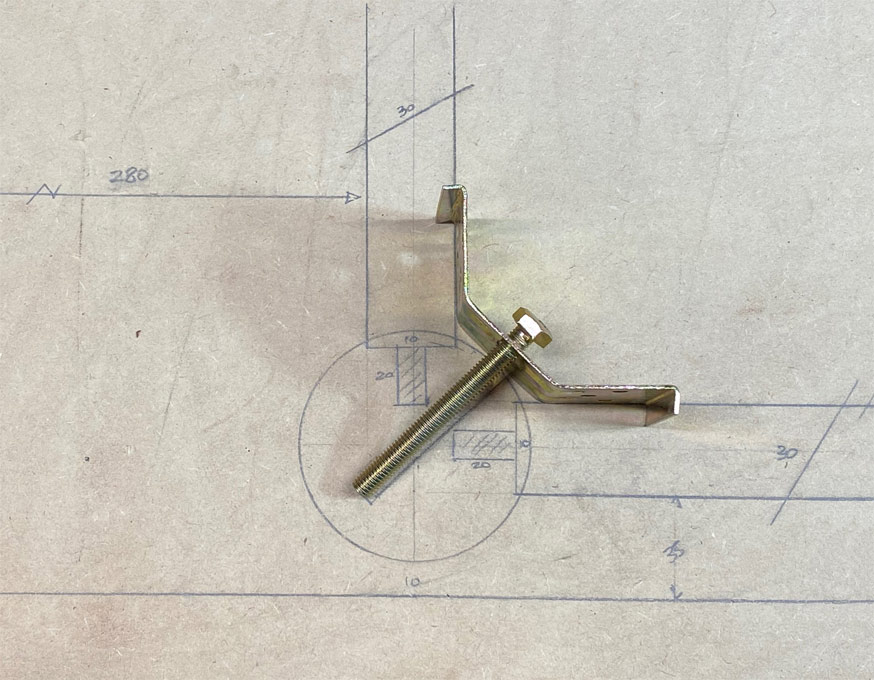

To facilitate the knock-down, a steel mechanical connector is being used ...

This requires the leg being tapped for a bolt, with the connector also screwed to the rails.

What follows is testing this out (some of the photos here have 75mm wide legs).

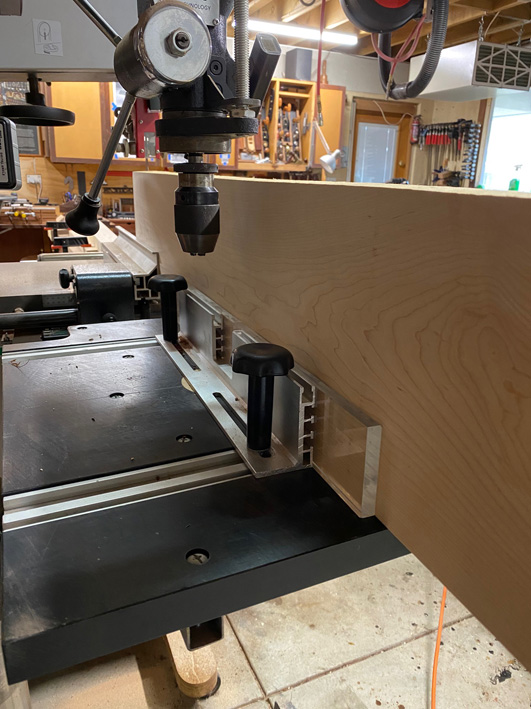

The 10mm x 55mm mortises in the legs were made with a router, and those in the rails made with a Domino.

The loose tenons were shaped on the router table using the new Woodpecker router bits ...

The legs were also mortised for the rails, themselves, to mate the two flush. Here I have gone down to a depth of 5mm.

This looks fine here ...

... but in future I shall mortise to a depth of 7mm. Once the leg is turned, there is minimal beauty depth ...

With the connector (ignore the chewed look - this was the result of trial-and-error) ...

And here is the completed piece to judge the aesthetics of the sizing ...

Thoughts?

Regards from Perth

Derek

The brief is to build an 8-seater dining table to replace our existing 6-seater. We will retain the 6 vintage bentwood chairs, and I recently completed 2 (DC 09) chairs for use as carvers. Our taste in furniture runs towards the minimalistic, the clean lines of mid century designs from the 1930s, gentle curves. What is needed in a design is a way to link and blend the chairs with the table. In part this will be aided by the wood used for the table top: both the carvers and the top are Rock Maple. Another element will be the presence of the curves in the chairs, which will extend to the table.

The old table was 200 years old and came with us from from South Africa when we moved to Sydney 40 years ago. The top was Yellow Wood (which resembles an aged Maple), and the legs were Stinkwood (a dark wood). The latter will be represented by Jarrah.

Another need for the new table is that is must be knock-down. We plan to move home in about 18 months, downsizing when I retire. The new home is similar in size, but with less garden to manage. Being knock-down cannot impose on the design, and cannot impact on the rigidity of the construction. Today I will show you what I came up with.

The old table was 1350mm (53") long, 850mm (33 1/5") wide and 775mm (30 1/2") high.

The new table will be 1780mm (70") long, 1020mm wide (40"), and 760mm (30") high.

I found a photo of a table with similar proportions. This table has rectangular legs, but its silhouette creates the illusion that the legs are round, which will be the case in this build.

When I began test-building the leg-rail build, the legs were to have a 75mm (3") diameter with a rail of similar width. The legs ended up too chunky, and were subsequently reduced to 60mm (2 3/8") diameter. I am considering reducing the rails to 60mm as well (they are 75mm in the photos), but am concerned about a drop in rigidity. Having stated this, the rails are 30mm wide, Jarrah, and this is quite substantial.

So to the construction ...

The rails (or stretcher) are connected to the legs with loose tenons. The tenons are glued to the end of the rails, but left unglued when connected to the legs.

To facilitate the knock-down, a steel mechanical connector is being used ...

This requires the leg being tapped for a bolt, with the connector also screwed to the rails.

What follows is testing this out (some of the photos here have 75mm wide legs).

The 10mm x 55mm mortises in the legs were made with a router, and those in the rails made with a Domino.

The loose tenons were shaped on the router table using the new Woodpecker router bits ...

The legs were also mortised for the rails, themselves, to mate the two flush. Here I have gone down to a depth of 5mm.

This looks fine here ...

... but in future I shall mortise to a depth of 7mm. Once the leg is turned, there is minimal beauty depth ...

With the connector (ignore the chewed look - this was the result of trial-and-error) ...

And here is the completed piece to judge the aesthetics of the sizing ...

Thoughts?

Regards from Perth

Derek